Derek Wilson Cain, PhD

- Assistant Professor in Medicine

- Member of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute

https://medicine.duke.edu/faculty/derek-wilson-cain-phd

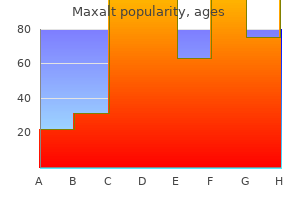

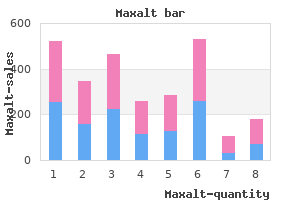

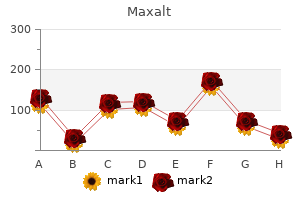

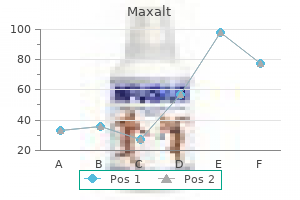

The lack of information on mechanisms with respect to noncancer health effects represents data gaps in the understanding of the health effects of dichloromethane pain treatment meridian ms generic maxalt 10 mg with mastercard. In the absence of this kind of knowledge myofascial pain treatment center reviews discount maxalt 10 mg without a prescription, and considering the pattern of response seen in the oral and inhalation studies (as described in Section 5 blaustein pain treatment center buy cheap maxalt 10 mg. Figure 5-3 shows the comparison between oral external and internal doses using this dose metric for the rat and for the human unifour pain treatment center hickory nc order 10 mg maxalt overnight delivery. Details of the models are as follows: Gamma and Weibull models restrict power ≥ 1; Log-logistic and Log-probit models restrict to slope >1 pain treatment center houston tx order maxalt visa, multistage model restrict betas ≥ 0; lowest degree polynomial with an adequate fit is reported (degree of polynomial noted in parentheses) pain medication for dogs spayed cheapest maxalt. This scaling factor was used because the metric is a rate of metabolism rather than the concentration of putative toxic metabolites, and the clearance of these metabolites may be slower per volume tissue in the human compared with the rat (that is, total 0. The drinking water exposures comprised six discrete drinking water episodes for specified times and percentages of total daily intake (Reitz et al. The mean and two lower points on the distributions of human equivalent doses derived from the Serota et al. Although a lower value in this distribution could be calculated, this would require proportionately greater iterations to achieve numerical stability. These studies provided dose response data for the hepatic effects of dichloromethane. The database also includes one-generation oral reproductive toxicity (General Electric Company, 1976) and developmental toxicity (Narotsky and Kavlock, 1995) studies that found no reproductive or developmental effects at dose levels in the range of doses associated with liver lesions. A two-generation oral exposure study is not available; however, a 181 two-generation inhalation exposure study by Nitschke et al. This study is limited in its ability to fully evaluate reproductive and developmental toxicity, however, because exposure was not continued throughout the gestation and nursing periods. No oral exposure studies that evaluated neurobehavioral effects in offspring were identified. This is a relevant endpoint given the neurotoxicity associated with dichloromethane exposure after oral and inhalation exposures (see Section 4. There are no oral exposure studies that include functional immune assays; however, there is a 4-week inhalation study of potential systemic immunotoxicity that found no effect of dichloromethane exposure at concentrations up to 5,000 ppm on the antibody response to sheep red blood cells (Warbrick et al. Choice of Principal Study and Critical Effect—with Rationale and Justification Figure 5-5 includes exposure-response arrays from some of the human studies that were evaluated for use in the derivation of the RfC. These effects include an increase in prevalence of neurological symptoms among workers (Cherry et al. However, these studies have inadequate power for the detection of effects with an acceptable level of precision. In addition, the outcome assessment was conducted a mean of 5 years after leaving the workplace, and so would underestimate health effects that diminish postexposure. Because of these limitations, these human studies of chronic exposures do not serve as an adequate basis for RfC derivation. The database of experimental animal dichloromethane inhalation studies includes numerous 90-day and 2-year studies, with data on hepatic, pulmonary, and neurological effects, (see Table 4-27) and reproductive and developmental studies (Table 4-28) (see summary in Section 4. The data from the subchronic studies are, however, used to corroborate the findings with respect to relevant endpoints. F) – Mennear F) – M) – – Cherry et Ott et al Dawley rat) – Dawley rat) Burek et al. Exposure response array for chronic (animal) or occupational (human) inhalation exposure to dichloromethane (log Y axis) (M = male; F = female). Exposure response array for subacute to subchronic inhalation exposure to dichloromethane (log Y axis) (M=male; F=female). Based on the results reviewed above, liver lesions (specifically, hepatic vacuolation) in rats are identified as the critical noncancer effect from chronic dichloromethane inhalation in animals. Vacuolization is defined as the process of accumulating vacuoles in a cell or the state of accumulated vacuoles and can reflect either a normal physiological response or an early toxicological process. As a normal physiological response, vacuolization is associated with the sequestration of materials and fluids taken up by cells, and also with secretion and digestion of cellular products (Henics and Wheatley, 1999). Vacuolization has also been identified as one of four principal types of chemical-induced injury (the other three being cloudy swelling, hydropic change, and fatty change) (Grasso, 2002). It is one of the most common responses of the liver following a chemical exposure; typically in the accumulation of fat in parenchymal cells, most often in the periportal zone (Plaa and Hewitt, 1998). The ability to detect subtle ultrastructural defects, such as vacuolization, early in the course of toxicity often permits identification of the initial site of the lesion and thus can provide clues to possible biochemical mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of liver injury (Hayes, 2001). Given the range of underlying causes of hepatocellular vacuolation (from normal physiological response to indicator of chemically induced toxicity), it is appropriate to take into consideration such factors as the characterization of vacuolization by the investigators. In the case of dichloromethane, hepatocellular vacuolation was characterized by study authors as correlating with fatty change (Burek et al. Dose-related increases in the incidence of hepatocellular vacuolation have been observed in rats and mice following both inhalation (Mennear et al. Accumulation of lipids in the hepatocyte may lead to the more serious liver effects observed following dichloromethane exposure, such as hepatic steatosis (fatty liver) reported in dogs (Haun et al. Given the liver findings for 188 dichloromethane in the database as a whole, the evidence is consistent with hepatic vacuolation as a precursor of toxicity. Accordingly, hepatic vacuolation is considered a toxicologically relevant and adverse effect. A decrease in fertility index was seen in the 150 and 200 ppm groups in a study of male Swiss Webster mice exposed via inhalation for 6 weeks prior to mating (Raje et al. Two types of developmental effects (decreased offspring weight at birth and changed behavioral habituation of the offspring to novel environments) were seen in Long-Evans rats following exposure to 4,500 ppm for 14 days prior to mating and during gestation (or during gestation alone) (Bornschein et al. Neurological impairment was not seen in lifetime rodent bioassays involving exposure to airborne dichloromethane concentrations of ≤2,000 ppm in F344 rats (Mennear et al. It should be noted, however, that these studies did not include standardized neurological or neurobehavioral testing. The only subchronic or chronic study in which neurobehavioral batteries were utilized found no effects in an observational battery, a test of hind-limb grip strength, a battery of evoked potentials, or brain, spinal cord, or peripheral nerve histology in F344 rats exposed to concentrations up to 189 2,000 ppm for 13 weeks, with the tests performed beginning 65 hours after the last exposure (Mattsson et al. Other effects associated with lifetime inhalation exposure to dichloromethane include renal tubular degeneration and renal tubular casts in F344 rats exposed to ≥2,000 ppm (Mennear et al. Derivation Process for RfC Values the derivation process used for the RfC parallels the process described in Section 5. As noted in the RfD discussion, the mechanistic issues with respect to noncancer health effects represent data gaps in the understanding of the health effects of dichloromethane. As noted in Table 5-5, the male data were not used because the overall response (comparing the 500 ppm to the control group) was lower, and because no data pertaining to the response pattern in the lower exposure groups (50 and 200 ppm) were provided. Simulations of 6 hours/day, 5 days/week inhalation exposures used in the Nitschke et al. Figure 5-7 shows the comparison between inhalation external and internal doses, using this dose metric for the rat and the human. Since a different set of samples was used for each dose, some stochasticity is evident as the human points (values) do not fall on smooth curves. Gamma and Weibull models restrict power ≥ 1; Log logistic and log-probit models restrict to slope >1, multistage model restrict betas ≥ 0; lowest degree polynomial with an adequate fit reported (degree of polynomial in parentheses). This scaling factor was used because the metric is a rate of metabolism rather than the concentration of putative toxic metabolites, and the clearance of these metabolites may be slower per volume tissue in the human compared with the rat. Estimated mean, first, and fifth percentiles of this distribution are shown in Table 5-7. Use of this value associated with a sensitive human population addresses the uncertainty associated with human toxicokinetic variability. The inhalation database for dichloromethane includes several well-conducted chronic inhalation studies. In these chronic exposure studies, the liver was identified as the most sensitive noncancer target organ in rats (Nitschke et al. The critical effect of hepatocyte vacuolation was corroborated in the principal study (Nitschke et al. Gross signs of neurologic impairment were not seen in lifetime rodent inhalation bioassays for dichloromethane at exposure levels up to 4,000 ppm (see Section 4. A two-generation reproductive study in F344 rats reported no effect on fertility index, litter size, neonatal survival, growth rates, or histopathologic lesions at exposures ≥100 ppm dichloromethane (Nitschke et al. Since exposure was not continuous throughout the gestation and nursing periods, however, it may not be representative of a typical human exposure and would not completely characterize reproductive and developmental toxicity associated with dichloromethane. Fertility index (measured by number of unexposed females impregnated by exposed males per total number of unexposed females mated) was reduced following inhalation exposure of male mice to 150 and 200 ppm dichloromethane 2 hours/day for 6 weeks (Raje et al. The available developmental studies are all single-dose studies that use relatively high exposure concentrations [1,250 ppm in Schwetz et al. In one of the single-dose studies, decreased offspring weight at birth and changed behavioral habituation of the offspring to novel environments were seen following exposure of adult Long-Evans rats to 4,500 ppm for 14 days prior to mating and during gestation (or during gestation alone) (Bornschein et al. A recent study used a similar approach for the evaluation of immunosuppression from acute exposures to trichloroethylene and chloroform (Selgrade and Gilmour, 2010). Although dichloromethane was not included in this study, Selgrade and Gilmour (2010) provide support for the methodological approach used by Aranyi et al. Increases of some viral and bacterial diseases, particularly bronchitis-related mortality, is also suggested by some of the cohort studies of exposed workers (Radican et al. Systemic immunosuppression was not seen in a 4-week, 5,000-ppm inhalation exposure study measuring the antibody response to sheep red blood cells in Sprague-Dawley rats (Warbrick et al. These studies suggest a localized, portal-of-entry effect within the lung rather than a systemic immunosuppression. There is an additional potential concern for immunological effects as suggested by a single acute inhalation study, specifically immunosuppressive effects that may be relevant for infectious diseases spread through inhalation. Additional comparison RfCs were derived based on neurological endpoints from human occupational exposures. The measured dichloromethane concentrations from personal breathing zone sampling of the exposed workers ranged from 28 to 173 ppm. There were no significant differences between exposed and unexposed workers based on visual analog scales of sleepiness, physical and mental tiredness, and general health or on tests of reaction time or digit substitution conducted at the beginning of a workshift. Exposed workers showed a slightly slower (but not statistically significant) score than the control workers on a reaction time test, but the scores did not deteriorate during the shift. During a workshift, the exposed workers deteriorated more on each of the scales than did the controls, and a significant correlation was shown between change in mood over the course of the shift and level of dichloromethane in the blood (correlation coefficients –0. Deterioration in the digit substitution tests at the end of the shift was also significantly related to blood dichloromethane levels (correlation coefficients = –0. Limitations of this study include lack of information on duration of exposures and evaluation of a limited number of endpoints. Retired aircraft maintenance workers, ages 55–75 years, employed in at least 1 of 14 targeted jobs. The evaluation included several standard neurological tests, including physiological measurement of odor and color vision senses, auditory response potential, hand grip strength, measures of reaction time (simple, choice, and complex), short term visual memory and visual retention, attention, and spatial ability. The exposed group had a 197 higher score on verbal memory tasks (effect size approximately 0. Given the sample size, however, the power to detect a statistically significant difference between the groups was low. An estimated exposure level from the study can be generated from the midpoint value from the 3 exposure range (82–236 ppm; midpoint = 159 ppm), converted to 552 mg/m. The animal-derived RfC is preferable to the human-derived RfC because of the uncertainties about the characterization of the exposure, influence of time since exposure, effect sizes, and statistical power in the epidemiologic studies. Specific uncertainties regarding the model structure are described in detail in Section 3. Since the numerical average of the mean kfC values for the four data sets included in the combined data set was 12. Therefore, for consistency, the distributions for all of the fitted parameters were rescaled by the ratio of the mean for DiVincenzo and Kaplan (1981) to the mean for the combined data set. Thus the impact of this model uncertainty appears to be modest for the noncancer assessment. Data were not available to perform a hierarchical Bayesian calibration in the rat. Thus, uncertainties in the rat model predictions had to be assessed qualitatively. To address these uncertainties, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine which model parameters most influence the predictions for a given dose metric and exposure scenario. The approach implemented was a univariate analysis in which the value of an individual model parameter was perturbed by an amount (Δ) in the forward and reverse direction. In equation 5-1, the sensitivity coefficients are scaled to the nominal value of x and f(x) to eliminate the potential effect of units of expression. Therefore, the sensitivity coefficient is a measure of the proportional (unitless) change in the output variable produced by proportional change in the parameter value. Parameters that have higher sensitivity coefficients have greater influence on the output variable. The results of the sensitivity analysis are useful for assessing uncertainty in model predictions, based on the level of confidence or uncertainty in the model parameter(s) to which the dose metric is most sensitive. The exposure conditions were set to be near or just below the lowest bioassay exposure resulting in significant increases in the critical effect. VmaxC for the rat was estimated by fitting to the pharmacokinetic data as described in Section 3 and Appendix C, subject to model structure/equation uncertainties as detailed above, and hence is known with less certainty than the physiological parameters. An additional uncertainty results from the lack of knowledge concerning the most relevant dose metric. The model and resulting distributions take into account the known nonchemical-specific variability in human physiology as well as total variability and uncertainty in dichloromethane-specific metabolic capability. Selection of the first percentile allows generation of a numerically stable estimate for the lower end of the distribution. The mean value of the human equivalent oral dose in Table 5-3 was about twofold higher than the corresponding first percentile values, and the mean value of human equivalent inhalation concentration in Table 5-7 was approximately threefold higher than the first percentile value.

These T cells are probably not involved in the plaque formation as such sciatica pain treatment guidelines buy 10mg maxalt overnight delivery, but they may cause plaque instability sacroiliac joint pain treatment exercises buy cheap maxalt, rupture pain medication for dogs with bad hips 10 mg maxalt free shipping, and subsequent clinical events pain treatment center johns hopkins purchase maxalt canada. The incidence of a disease is the number of new diagnoses that occur in a population in a given time period cape fear pain treatment center dr gootman order 10 mg maxalt overnight delivery. The prevalence is the number of people who have the disease and so is determined by the incidence and duration of the illness pain treatment endometriosis trusted 10 mg maxalt. The criteria used to define a disease, methods used to identify people with a specific condition, study area, as well as secular changes in rates can contribute to the variability in rates for a specific disease that may be seen among studies. A recent review of epidemiological studies covering 24 specific autoimmune diseases estimated that approximately 3% of the population in the United States suffers from an autoimmune disease (Jacobson et al. This estimate is likely to be low, as for many diseases our knowledge of basic epidemiology is quite limited or based on studies conducted 30 or more years ago, and some diseases. A revised estimate of the prevalence of autoimmune diseases presented in a recent report of the United States National Institutes of Health (2000) is 5–8%. Many specific autoimmune diseases are relatively rare, with an estimated incidence of less than 5 per 100 000 persons per year or an estimated prevalence of less than 20 per 100 000 (Table 7). Diabetes mellitus type 1 rates are for children and adolescents (age <20 years); all other rates are for adult populations. Two autoimmune diseases, diabetes mellitus type 1 and myocarditis, are most commonly seen in children and adolescents. Addison disease, multiple sclerosis, and vitiligo occur most often in young adults (and teenagers, in the case of vitiligo) (Table 7). The autoimmune thyroid diseases, lupus, systemic sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis usually occur in late reproductive and early-postmenopausal years, while some other diseases. Almost all autoimmune diseases that occur in adults dispropor tionately affect women. However, there is considerable variability in the extent of female predominance and no clear relation between degree of female predominance and type of disease or age at onset (Table 7). More than 85% of patients with Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, the autoimmune thyroid diseases, and primary biliary cirrhosis are female, compared with 65–75% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. The extent to which ethnic, racial, or geographic variability in disease incidence or severity occurs has been well characterized for only the few autoimmune diseases that have been the subject of numerous epidemiological studies. In diabetes mellitus type 1, multiple sclerosis, and hyperthyroidism, rates are higher among whites than among minority groups (Kurtzke et al. African Americans and other minority groups in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom are at higher risk of systemic lupus erythe matosus compared with whites (Hopkinson et al. Severity of these diseases is worse in these groups, too, with increased disease activity, increased organ 90 Epidemiology damage (particularly renal involvement), and higher mortality risks (Laing et al. Thus, it may permit the detection of genes or environmental factors that can inform preventive action. Co-morbidity can be observed at a number of levels, including the individual, the household, the family (genetically related), and population levels. Animal models suggest that both genetic and environmental factors are important in co-morbidity, and of particular interest is the way in which environmental factors can modify genetic suscep tibility. In both cases, early immune stimulation leads to lower incidence of diabetes, showing how genetic susceptibility to multiple autoimmune disorders may be disguised by environmental factors. Data pertaining to co-morbidity of autoimmune diseases in humans are surprisingly sparse. Few studies are population-based, and few are of sufficient size to address potentially important bio logical associations, given the relative rarity of many diseases (Scofield, 1996). A recent unpublished review of co-morbidity of rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus type 1, multiple sclerosis, Crohn disease, and autoimmune thyroid disease found evidence of an increased incidence of autoimmune thyroid disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and in autoimmune diabetes (E. Studies in this area are also few and most of a small size, which makes control of con founding difficult. One study of the household showed that those living with subjects suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus were more likely to have related autoantibodies (DeHoratius et al. The study was not able to fully distinguish between a genetic and environmental relationship, but it raises many intriguing ques tions. These studies are most feasible for the autoantibodies associated with the most common autoimmune diseases: diabetes mellitus type 1, autoim mune thyroid disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. Important issues with respect to interpreting these types of studies include the type of test used and definition of a “positive” result. Approximately 5% of high-risk groups (defined on the basis of family history or genetic susceptibility) have two or more of these antibodies, compared with 0. The presence of diabetes-related autoantibodies is strongly associated with subsequent risk of developing disease. The prevalence of antithyroglobulin and antithyroid peroxidase antibodies (formerly called antimicrosomal antibodies) increases with age, and the antibodies are more common among women than among men (Hawkins et al. In the recent population based sample in the United States, approximately 18% of people ages 12–80 who were not taking thyroid medications and did not report a history of thyroid disease or goitre had one or both of these antibodies. In the cross-sectional analysis of the full population (including those with thyroid disease), antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, but not antithyroglobulin antibodies, were highly predictive of hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism (defined on the basis of thyroid stimulating hormone and thyroxine [T4] levels). The predictive ability of antithyroid peroxidase antibodies for the subsequent development of hypothyroidism was also seen in a longitudinal study in the United Kingdom (Vanderpump et al. In the Pima Indians, a population with an extremely high incidence of rheumatoid arthritis, the prevalence of rheumatoid factor is higher in females than in males (Enzer et al. Rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies have been shown to be predictive of the development of rheumatoid arthritis (del Puente et al. Several large studies of antinuclear antibodies in the general population have been conducted using blood donors (Fritzler et al. Similar estimates were seen in these studies, with a prevalence of approx imately 25–30% at a titre of 1:40 and 3–4% at a titre of 1:320. The prevalence of antinuclear antibodies is lower in children than in adults, but is fairly constant through the reproductive years. There are limited, and somewhat conflicting, data comparing prevalence of high-titre antinuclear antibodies by sex (Craig et al. None of these studies was able to provide data pertaining to ethnic differences in the prevalence of antinuclear antibodies. We do not currently have data pertaining to the predictive ability of antinuclear antibodies with respect to development of lupus. A complex relation is seen between dietary iodine and prevalence of antithyroid antibodies, with increased prevalence reported in relation to iodine deficiency and to excess intake. Smoking history has been associated with the prevalence of rheumatoid factor in several studies (Regius et al. These studies reported an increased prevalence of rheumatoid factor among smokers. A similar association was also seen between smoking and antinuclear antibodies in one study (Regius et al. With respect to thyroid antibodies, however, smoking was associated with a decreased prevalence of antithyroid peroxidase antibodies in a study of 759 women in the Netherlands (Strieder et al. Anti-glutamic acid decarbox ylase antibodies were also found at an increased prevalence among these workers (Langer et al. There are also other studies on pesticide immunotoxicity following exposure to the pesticide mancozeb (Colosio et al. Both of these studies suggest a slight immuno stimulatory effect exerted by mancozeb. Small studies examining pentachlorophenol (McConnachie & Zahalsky, 1991; Colosio et al. There was a 2-fold increased prevalence with history of exposure to insecticides and herbicides, but not with exposure to fungicides or algicides. This association was seen with several specific organochlorine pesticides, but was not seen in analyses of higher-titre antinuclear antibodies. It is also important to realize that normal healthy individuals possess natural autoantibodies as well as autoreactive T and B cells to provide a necessary and protective immunological homeostasis (Avrameas, 1991; Schwartz & Cohen, 2000). At the present time, it is not precisely known why on certain occasions autoimmune responses can lead to pathological conditions. Another important consideration is that mech anisms of systemic allergy may resemble those of autoimmune reactions, at least to some extent. Compounds can induce the release of neoantigens (cryptic epi topes) or alter autoantigens so that they appear foreign (Griem et al. Specificity of an immune response induced by a compound may be initially directed exclusively towards this neoantigen, but after a certain time it spreads to include autoantigen-directed responses. Individual properties of patients may determine whether the immune response is eventually more allergy-like or more autoimmune-like in nature. Whether exposure to a chemical results in immune-related diseases may depend more on a patient’s individual predisposing characteristics and circumstances of exposure than on the characteristics of the chemical itself (Lehmann et al. The 96 Mechanisms of Chemical-Associated Autoimmune Responses multifactorial nature of the process may explain why only relatively few patients develop adverse clinical responses. The complexity of chemical-induced systemic allergy and auto immunity is a major hurdle for the development of models pre dictive for such adverse effects of chemicals. To illustrate the possible mechanisms of chemical-induced autoimmunity, in particu lar regarding initiation of processes, it is reasonable to consider results of studies with allergenic drugs as well. Mechanisms through which chemicals cause sensitization of the immune system are very diverse, but they can mostly be categorized according to the general strategy that is followed by the immune system (Janeway & Medzhitov, 2002; Hoebe et al. According to this strategy, immunization occurs only when cells of the adaptive immune system (T and B lymphocytes) encounter antigen-specific signals (providing so-called signal 1 to the lympho cyte) from antigen-presenting cells in combination with additional, adjuvant-like costimulatory signals (collectively called signal 2). Once sensitized, T cells may activate various effector mechanisms that in turn may cause protective immunity or, depending on the antigen that is recognized and under certain circumstances, adverse. All steps in this process are strongly regulated by a number of factors, including immune, neuroendocrine, and environmental factors (see Fig. Together, this strategy aims to tailor the immune response so as to effectively get rid of the initiating antigen and at the same time to prevent the immune response from persisting or possibly proceeding to adverse effects. For instance, chemicals may interfere with antigen-specific stimulation (signal 1) by forming neoantigens (section 7. Chemicals may also elicit adjuvant-like processes, reminiscent of danger signals, leading to increased costimulation, and thus provide signal 2 to lymphocytes (section 7. Once a low molecular weight compound has bound to a larger protein, a so-called hapten–carrier complex is formed. In the case of hapten–carrier complex 98 Mechanisms of Chemical-Associated Autoimmune Responses formation, the binding between the chemical and the carrier protein is supposed to be covalent in nature. In contrast to most chemi cals, such as industrial chemicals, sensitizing drugs, however, are usually not chemically reactive, and it is hypothesized that they need to be bioactivated through metabolism to bind covalently to a carrier and become immunogenic. In this case, T cell help is called non-cognate help, because T and B cells recognize different antigens. This hypothesis is supported by studies with allergenic chemicals such as trinitrochlorobenzene (Weltzien et al. Based on these findings, the pharmacological interaction concept has been formulated (Pichler, 2002). However, whether drugs are also capable of inducing adverse immune reactions by this mechanism is as yet unknown. From these findings, it can be inferred that drug-induced T cells can also react with autoantigens through cross-reactivity. Examples of non-tolerant epitopes are sequestered epitopes and cryptic epitopes (Sercarz et al. Anatomically sequestered epitopes (as part of an antigen) are part of immunologically privileged sites, such as the eye, brain, and testis, but also intracellular epitopes that normally do not come in contact with lymphocytes. As these antigens do not come in contact with the developing immune system, tolerance does not exist. As a consequence of tissue damage, however, antigens may be released in the system, and naive specific T cells may become activated. As these T cells are then reactive to self-proteins, a destructive auto immune response may follow. In principle, chemicals, once being reactive and membrane damaging, may induce autoimmune responses in this manner. Foreign proteins as well as self-proteins contain dominant and cryptic epitopes (Sercarz et al. T cells that recognize dominant epitopes with too high an affinity or avidity have a high chance of being eliminated during the intrathymic selection process, whereas T cells that are specific to cryptic epitopes will usually not encounter their epitope in the thymus. Hence, these T cells will not be eliminated in the thymus and appear in the peripheral system. The underlying mechanisms are unknown, but may include (i) changes in antigen processing, (ii) structural alterations of the antigen, (iii) interference with antigen processing. Administration of cyclosporin to newborn mice has been shown to abrogate production of mature thymocytes and cause various organ-specific autoimmune diseases, including thyroiditis, oophoritis, orchitis, insulitis, and adrenalitis (Sakaguchi & Sakaguchi, 1989). A recently suggested mode of action of the induction of immune responsiveness as a result of drug exposure also involves inter ference with central tolerance induction in the thymus. In other words, signal 2 can be considered to be more decisive than signal 1 for inducing an immune response. Signal 2 or co-stimulation is provided by non-antigen-specific receptor–ligand interactions and is required for optimal sensitization of both T and B lymphocytes. Over the past years, more B7 homologues and ligands have been discovered and new pathways have been described that seem to be important in regulating adaptive immune responses, resulting in the recognition of a B7 family (Henry et al. The signalosome is directly related to the immunological synapse and organized as a flexible aggregation of lipid rafts at the interface between T cells and antigen-presenting cells. Altogether, it is important to realize that the interaction of antigen-presenting cells and T cells involves a complex set of interacting and modulatory receptor–ligand couples. In addition, a number of cytokines are regarded as inducers and mediators of co-stimulatory help.

Gy per fraction to a typical dose of 70 Gy in 7 weeks with single-agent cisplatin given every 3 weeks at 100 2Particular attention to speech and swallowing is needed during therapy hip pain treatment options buy maxalt online now. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal slightly modified (eg treatment for acute shingles pain maxalt 10mg otc, <2 a better life pain treatment center golden valley az cheap 10 mg maxalt overnight delivery. An additional 2–3 doses can be added depending is standard fractionation plus 3 cycles of chemotherapy pain treatment center of franklin tennessee purchase maxalt master card. Lancet Oncol accelerated hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiation therapy for 2012;13:145-153) pain treatment ibs cheap maxalt 10mg with visa. Int J Radiat Oncol schedules of cisplatin shalom pain treatment medical center effective 10 mg maxalt, or altered fractionation with chemotherapy are efficacious, and there is no consensus Biol Phys 2010;76:1333-1338. An of radiotherapy with or without concomitant chemotherapy in locally advanced head additional 2–3 doses can be added depending on clinical circumstances. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal Chemoradiation should be performed by an experienced team and should include cancer. N2 or N3 nodal disease, perineural invasion, vascular embolism, lymphatic lIn highly select patients, re-resection (if negative margins are feasible and can invasion (See Discussion). Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. Proton therapy can be considered when Monday–Friday in 7 weeks normal tissue constraints cannot be met by photon-based therapy. All current smokers should be advised to quit smoking, and former smokers should be advised to remain. Lymph node metastasis in maxillary sinus 3For doses >70 Gy, some clinicians feel that the fractionation carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;46:541-549) and (Jeremic B, Nguyen-Tan should be slightly modified (eg, <2. Elective neck irradiation in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma some of the treatment) to minimize toxicity. Data indicate that accelerated fractionation does not ofer improved efcacy over conventional fractionation. For any chemoradiation approach, close attention should be paid to published reports for the specifc chemotherapy agent, dose, and schedule of administration. J Clin Oncol on the basis of time interval since original radiotherapy, anticipated volumes to be 2010;28(Suppl 15):Abstract 5507. Concomitant chemoradiotherapy versus tissue constraints cannot be met by photon-based therapy. When the goal of treatment is curative 8For doses >70 Gy, some clinicians feel that the fractionation should be slightly and surgery is not an option, reirradiation strategies can be considered for modified (eg, <2. Postoperative irradiation with or without after the initial radiotherapy; can receive additional doses of radiotherapy of at least 60 Gy; and can tolerate concurrent chemotherapy. Organs at risk for toxicity concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J should be carefully analyzed through review of dose-volume histograms, and Med 2004;350:1945-1952. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy consideration for acceptable doses should be made on the basis of time interval and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Defining risk levels in locally advanced head cannot be met by photon-based therapy. All current smokers should be advised to quit smoking, and former smokers should be advised to remain abstinent from dDetermined with appropriate immunohistochemical stains. Patient should be prepared for neck dissection at time of open biopsy, if indicated. Consider higher dose to 60–66 Gy to particularly suspicious areas Low to intermediate risk: Sites of suspected subclinical spread 4 ◊ 44–50 Gy (2. In general, the use of concurrent chemoradiation carries a high toxicity burden; altered fractionation or multiagent chemotherapy will likely further increase the toxicity burden. For any chemoradiation approach, close attention should be paid to published reports for the specific chemotherapy agent, dose, and schedule of administration. Chemoradiation should be performed by an experienced team and should include substantial supportive care. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. All current smokers should be advised to quit smoking, and former smokers should be advised to remain abstinent from smoking. When the goal of treatment is curative and surgery is not an option, reirradiation strategies can be considered for patients who: develop locoregional failures or second primaries at ≥6 months after the initial radiotherapy; can receive additional doses of radiotherapy of at least 60 Gy; and can tolerate concurrent chemotherapy. Reirradiation of head and neck cancers with intensity modulated radiation therapy: Outcomes and analyses. Adjuvant radiotherapy versus observation alone for patients at risk of lymph-node field relapse after therapeutic lymphadenectomy for melanoma: a randomised trial. Mucosal melanoma of the nose and paranasal sinuses, a contemporary experience from the M. Further reimaging as indicated based on worrisome or equivocal signs/symptoms, smoking history, and areas inaccessible to clinical examination. Routine annual imaging (repeat use of pretreatment imaging modality) may be indicated in areas difcult to visualize on exam. For additional cessation support and resources, smokers should include endoscopic inspection for paranasal sinus disease. The surgical procedure should not be modifed based on any response observed as a result of prior therapy except in instances of tumor progression that mandate a more extensive procedure in order to encompass the tumor at the time of defnitive resection. It is critical that multidisciplinary evaluation and treatment be coordinated and integrated prospectively by all disciplines involved in patient care before the initiation of any treatment. Assessment of Resectability Tumor involvement of the following sites is associated with poor prognosis or function* or with T4b cancer (ie, unresectable based on technical ability to obtain clear margins). None of these sites of involvement is an absolute contraindication to resection in selected patients in whom total cancer removal is possible. Involvement of the pterygoid muscles, particularly when associated with severe trismus or pterygopalatine fossa involvement with cranial neuropathy;*. Gross extension of the tumor to the skull base (eg, erosion of the pterygoid plates or sphenoid bone, widening of the foramen ovale);. Direct extension to the superior nasopharynx or deep extension into the Eustachian tube and lateral nasopharyngeal walls;. Encasement is usually assessed radiographically and is defned as a tumor surrounding the carotid artery by 270 degrees or greater;. Direct extension to mediastinal structures, prevertebral fascia, or cervical vertebrae; and*. The primary tumor should be considered surgically curable by appropriate resection using accepted criteria for adequate excision, depending on the region involved. When gross invasion is present and the nerve can be resected without signifcant morbidity, the nerve should be dissected both proximally and distally and should be resected to obtain clearance of disease (See Surgical Management of Cranial Nerves page 4 of 8). Frozen section determination of the proximal and distal nerve margins may prove helpful to facilitate tumor clearance. Adequate resection may require partial, horizontal, or sagittal resection of the mandible for tumors involving or adherent to mandibular periosteum. The extent of mandibular resection will depend on the degree of involvement accessed clinically and in the operating room. Frozen section examination of available marrow may be considered to guide resection. Successful application of these techniques requires specialized skills and experience. Margin assessment may be in real time by frozen section or by assessment of formalin-fxed tissues. Tumor-free margins are an essential surgical strategy for diminishing the risk for local tumor recurrence. Conversely, positive margins increase the risk for local relapse and are an indication for postoperative adjuvant therapy. Clinical pathologic studies have demonstrated the signifcance of close or positive margins and their relationship with local tumor recurrence. Obtaining additional margins from the patient is subject to ambiguity regarding whether the tissue taken from the surgical bed corresponds to the actual site of margin positivity. Frozen section margin assessment is always at the discretion of the surgeon and should be considered when it will facilitate complete tumor removal. The achievement of adequate wide margins may require resection of an adjacent structure in the oral cavity or laryngopharynx such as the base of the tongue and/or anterior tongue, mandible, larynx, or portions of the cervical esophagus. In general, frozen section examination of the margins will usually be undertaken intraoperatively, and, importantly, when a line of resection has uncertain clearance because of indistinct tumor margins, or there is suspected residual disease (ie, soft tissue, cartilage, carotid artery, mucosal irregularity). With this approach, adequacy of resection may be uncertain and is assessed under high magnifcation and confrmed intraoperatively by frozen sections. Such margins would be considered “close” and may be inadequate for certain sites such as3 oral tongue. The margins may be assessed on the resected specimen or alternatively from the surgical bed with proper orientation. If carcinoma in situ is present and if additional margins can be obtained that is the favored approach. Carcinoma in situ should not be considered an indication for concurrent postoperative chemoradiation. The primary tumor should be assessed histologically for depth of invasion and for distance from the invasive portion of the tumor to the margin of resection, including the peripheral and deep margins. The pathology report should be template driven and describe how the margins were assessed. The report should provide information regarding the primary specimen to include the distance from the invasive portion of the tumor to the peripheral and deep margin. If the surgeon obtains additional margins from the patient, the new margins should refer back to the geometric orientation of the resected tumor specimen with a statement by the pathologist that this is the fnal margin of resection and its histologic status. Primary closure is recommended when appropriate but should not be pursued at the expense of obtaining wide, tumor-free margins. Reconstructive closure with local/regional faps, free-tissue transfer, or split-thickness skin or other grafts with or without mandibular reconstruction is performed at the discretion of the surgeon. These guidelines apply to the performance of neck dissections as part of treatment of the primary tumor. In general, patients undergoing surgery for resection of the primary tumor will undergo dissection of the ipsilateral side of the neck that is at greatest risk for metastases. For those patients with tumors at or approaching the midline, both sides of the neck are at risk for metastases, and bilateral neck dissections should be performed. Patients with advanced lesions involving the anterior tongue, foor of the mouth, or alveolus that approximate or cross the midline should undergo contralateral selective/modifed neck dissection as necessary to achieve adequate tumor resection. For a depth less than 2 mm, elective dissection is only indicated in highly selective situations. For a depth of 2–4 mm, clinical judgment (as to reliability of follow-up, clinical suspicion, and other factors) must be utilized to determine appropriateness of elective dissection. Recent randomized trial evidence supports the efectiveness of elective neck dissection in patients with oral cavity cancers >3 mm in depth of invasion. For example, a T4a glottic tumor with extension through the cricothyroid membrane and subglottic extension should include a total thyroidectomy and pretracheal and bilateral paratracheal lymph node dissection. Accuracy of sentinel node biopsy for nodal staging of early oral carcinoma has been tested extensively in multiple single-center studies and two multi-institutional trials against the reference standard of immediately performed neck dissection or subsequent extended follow-up with a pooled estimate of sensitivity 5-10 of 0. While direct comparisons with the policy of elective neck dissection are lacking, available evidence points towards comparable survival outcomes. Procedural success rates for sentinel node identifcation as well as accuracy of detecting occult lymphatic metastasis depend on technical expertise and experience. Hence, sufcient caution must be exercised when ofering it as an alternative to elective neck dissection. This is particularly true in cases of foor-of-mouth cancer where accuracy of sentinel node biopsy has been found to be lower than for other locations such as the tongue. Neck disease in an untreated neck should be addressed by formal neck dissection or modifcation depending on the clinical situation. Surveillance All patients should have regular follow-up visits to assess for symptoms and possible tumor recurrence, health behaviors, nutrition, dental health, and speech and swallowing function. The significance of “positive” margins in surgically resected epidermoid carcinomas. Microscopic cut-through of cancer in the surgical treatment of squamous carcinoma of the tongue. Sentinel lymph node biopsy accurately stages the regional lymph nodes for T1-T2 oral squamous cell carcinomas: results of a prospective multi-institutional trial. Sentinel node biopsy in head and neck squamous cell cancer: 5-year follow-up of a European multicenter trial. Sentinel node biopsy for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx: a diagnostic meta analysis. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for T1/T2 oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma—a prospective case series. Occult metastases detected by sentinel node biopsy in patients with early oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas: impact on survival. Sentinel node biopsy as an alternative to elective neck dissection for staging of early oral carcinoma. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in cN0 squamous cell carcinoma of the lip: A retrospective study. Standards for target defnition, dose specifcation, fractionation (with and without concurrent chemotherapy), and normal tissue constraints are still evolving. Close cooperation and interdisciplinary management are critical to treatment planning and radiation targeting, especially in the postoperative setting or after induction 9 chemotherapy.

Monroe Ammonia on Pt(100) Electrode: First (Department of Engineering Science pain treatment guidelines 2014 order maxalt paypal, University Principles Study – D xiphoid pain treatment purchase maxalt 10mg with visa. Duoss (Lawrence Pt Alloy Nanoparticles for Hydrogen Livermore National Laboratory) Oxidation and Evolution – D pain treatment center bismarck order maxalt 10mg line. Tryk (Fuel 15:00 1966 Electrostatics to Electrodynamics Via an Cell Nanomaterials Center pain treatment in pancreatitis maxalt 10 mg without prescription, University of Additional Frame of Reference – G low back pain treatment kerala discount maxalt 10mg without a prescription. Iiyama (Fuel Cell Nanomaterials Water Desalination Applications: Role Center pain medication for dog injury proven 10 mg maxalt, University of Yamanashi) of the Electrosorption Resistance and 09:20 1957 Anion Exchange Membranes with Low Non-Electrostatic Binding in the Porous Hydration Conditions from an Ab Initio Electrodes – Y. Hickner (The Pennsylvania Polyoxometallates and Nanostructured Metal State University), C. Bae (Rensselaer L04 Oxides in Effcient Electrocatalysis, Energy Polytechnic Institute), S. Paddison (University Conversion, and Charge Storage of Tennessee, Knoxville), and M. Tuckerman Physical and Analytical Electrochemistry / Energy Technology (New York University) Trinity 2, Dallas Sheraton Hotel 09:40 1958 Strain-Induced Ionic Conductivity of Cubic Li6. Polyoxometallates and Nanostructured Metal Oxides in Effcient Moradabadi (Technische Universität Darmstadt, Electrocatalysis, Energy Conversion, and Charge Storage 3 – Freie Universität Berlin) and P. Kuo (Colorado School of Mines) 10:20 1959 (Invited) the Electronic Structure Underlying Electrochemistry of Two-Dimensional 08:40 1975 (Invited) Nanofbrous Doped Tin Oxide Materials – Y. Song 09:10 1976 Preparation of Carbon Metal Oxide (McGill University) Composites for Hybrid Supercapacitor Applications – S. Growth Mechanisms at Li-O2 Battery Ferraris (University of Taxas at Dallas) Discharge Conditions Using Ab Initio Computations – J. Sambath Kumar (Department of Materials Chair(s): Jose Ramon Galan-Mascaros, Pawel J. Botton (McMaster Noto University) 11:20 1979 (Invited) Photo-Electrode Hybrid Materials. Kim (Korea Electrocatalysis, Energy Conversion, and Charge Storage 5 – Institute of Science and Technology) 14:00 – 15:30 Chair(s): Beatriz Roldan Cuenya and Frederic Maillard. Wu (Harbin Engineering University) (West Virginia University) 14:40 1981 (Invited) Charge Carriers Behaviour in Sensors, Actuators, and Microsystems General Solar Energy Harvesting & Converting M01 Session Semiconducting Systems. Solarska (University of Warsaw) Nanosensors – 08:00 – 12:00 15:10 1982 Purely Protonic Solar Cells Fabricated from Photoacid-Modifed Ion-Exchange Chair(s): Jessica E. Ardo (University of California, Irvine) 08:00 2004 Nanocrystalline Electro-Chemo-Mechanical Actuator Operating at Room Temperature – E. Lubomirsky (Weizmann Institute of Electrocatalysis, Energy Conversion, and Charge Storage 6 – Science) 16:00 – 17:30 08:20 2005 (Invited) Sensing, Measuring and Imaging Chair(s): Renata Anna Solarska and Daniel Guay Surface Charge with Nanoscale Pipettes – L. Baker (Department of Chemistry, Indiana 16:00 1983 (Keynote) Use of Conducting Metal Oxides to University) Modulate Charge Density Gradients in Ionic 09:00 2006 Cobalt Containing Zeolitic Imidazolate Liquids – K. Blanchard (Michigan State University) Carbon Nanofbers As Free-Standing Film 16:40 1984 (Invited) Oxygen Evolution and Reduction Sensor for Electrochemical Detection of on La0. Saha Hydrogen Sulfde By Platinum-Modifed (Washington State University Vancouver), and Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Sensors – P. Salmani Rezaie Vancouver) (Sharif University of Technology) Sensors for Precision Medicine IoT Sensors – 14:00 – 17:00 M03 Sensor Chair(s): Bryan A. Nagahara Trinity 4, Dallas Sheraton Hotel 14:00 2013 Embedded Ceramic-Based Passive Wireless Sensors for Precision Medicine Session 1 – 08:00 – 12:40 Sensors for Harsh-Environment Applications Chair(s): Praveen K. Sabolsky (West 08:00 2069 (Invited) Multifunctional Nanoplatforms for Virginia University, U. Palakurthi (West Virginia 08:40 2070 A Carbon Nanotube-Based Impedimetric University), D. Ramasamy (University of Sierros (West Virginia University) Georgia) 14:20 2014 Millimetre-Wave Bow-Tie Reconfgurable 09:00 2071 (Invited) Nanozyme Integrated Microfuidic Antenna for 5G Applications – T. Lin 14:40 2015 Development of a Wireless Surface Acoustic (Florida International University) Wave Methane Sensor Using a Metal 09:40 Break Organic Framework As a Sensing Layer for Natural Gas Pipelines – J. Lee Energy Technology Laboratory) (Chungnam National University) 15:00 2016 Distributed Fiber Optic pH Sensor for the 11:00 2074 (Invited) Nano Composite Platforms: Application in the Wellbore – F. Cho (Korea Electronics Technology Technologies Using Carbon Nanomaterials Institute), and M. Munje (The Composites As Electrode Materials for Fuel University of Texas at Dallas), S. Li (Dalian Chatterjee (Institute of Chemical Technology) Institute of Chemical Physics), and I. Vankelecom (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) 17:00 2082 (Invited) Modularized Inexpensive Detection of Biomarkers for Medical Applications – P. Manthiram (The University of Z01 All Divisions Texas at Austin) Lone Star B/C, Dallas Sheraton Convention Center. Nakamura Electrolyte Based on Kinetic Energy Barriers (National Insititute of Technology Nagaoka As Local Structure Variations By First College), N. Boosting Li+transport of LiV O Via 3 8 Matsumoto (Kanagawa University) Ca Doping – Y. Yao Hierarchically Porous Co-Zn-N-C As (National Institute of Technology, Kagawa Efcient Catalyst for Acidic Oxygen College) Reduction Reaction – Z. Kusumoto (Graduate School of and Passivation Film Chemistry Relevant Engineering Science, Osaka University), J. Hill (Lewis Science, Osaka University, Research Center for University, Department of Chemistry), A. Qiao (South Dakota State for Anode Current Collector in Oxygen University) Atmosphere – H. Naval University, Republic of Korea) Research Laboratory, Surface Chemistry Branch. Lee Hydrogen Doped Sputtered Boron Carbon (Chungnam National University, Republic of Nitride Thin Films – S. Park (Dept Subtractive Etching for Cu High Density of Materials Science Engineering, Yonsei Interconnects – G. Albin Electrochemically-Mediated Desalination (Department of Engineering, Norfolk State – C. Kim on Sapphire Substrates with Diferent AlN 2 2 (Chungnam National University, Republic Layers Inserted – K. Yoo (Korea Institute of Materials Bun (The University of Cambodia) Science), and J. Nersisyan (Rapidly Solidifed Materials Lee (Chungnam National University, Republic Research Center), and J. Mottaghizadeh (University of California, California) Irvine, National Fuel Cell Research Center), M. Jabbari (University of California, Irvine), and Various Formulation Conditions for High J. Brouwer (National Fuel Cell Research Center, Temperature Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cell University of California, Irvine) – D. Labata (University of California a Durability Testing of 1000 h Under High Merced) and P. Mehrazi (University of California Electrocatalysts for the Hydrogen Evolution Merced) and P. Roa Morales (Universidad Nanocomposite Anode for Improved Autónoma del Estado de México), and M. Thin Film with Redox-Active Linkers: Okiei (University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria), Development and Charge Transport C. Bhunia (National Institute of Technology Ojobe (University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria) Puducherry), H. Nanocomposite Media for Organic Pollutant Smith (San Diego State University) Degradation – S. Keleher (Lewis University, Department of of Metal Nanoparticle-Infused Biopolymer Chemistry) Matrices – D. Wang (Univeristy of North Transfer Type Open Circuit Potential Based Texas) Glucose Sensor Utilizing Microneedle Type. Lee (The University of Transfer to Control Binding Strength in North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Tokyo University H-Bond Dimers – H. Webb (Department of by Bio-Logic – City View 8, Sheraton Chemistry University of Texas at Austin), Hotel and R. Chura (Lewis University, Expo and Resume Review – Lone Star Department of Biology), and J. Keleher (Lewis University, Department of Chemistry) B/C, Sheraton Convention Center 1530h. Session – Lone Star B/C, Sheraton Prisbrey (University of Utah) Convention Center. Park (Dept of Materials Science A01 Joint General Session Engineering, Yonsei University) Energy Technology / Battery. Varman (Arizona Chair(s): Mariappan Parans Paranthaman and Jie Xiao State University), and T. Soundappan (Navajo Technical University) 08:00 69 Highly Concentrated Aqueous Gel. Ramesh Laboratory) (Norfolk State University) 08:20 70 Layered Ionic Conductor Na Zn TeO : 2 2 6. Doef (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) 09:00 72 Evaluation of Polymeric Binders in Aqueous Electrolyte Environment – G. Wu (Aquion Energy) 09:20 73 A High-Performance Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Enhanced By Graphene Oxide Doped By Redox Species – X. Sabolsky and Rahul Singhal University) 14:40 84 Fabrication and Supercapacitive Properties 10:00 75 Realizing an Asymmetric Supercapacitor of Thick Nanostructured Anodic Films on Employing Carbon Nanotubes Anchored 304 Stainless Steel – Y. Shukla (Indian Institute of Science) 15:00 85 Electrochemical Efects of Annealing Temperature on Anodic 304 Stainless Steels 10:20 76 Role of Oxygen Vacancy in Copper-Cobalt – Y. Hisatsune (School of Engineering, Tokyo the Use of a Quasi-Reference Electrode Institute of Technology), T. Kakushima (University of Manchester) (Tokyo Institute of Technology) 15:40 87 Graphene like Porous Carbon Sheets Derived 11:00 78 Elastic Cu@Ppy Sponge for Hybrid Device from Hibiscus Cannabinus As a Versatile with Energy Conversion and Storage – Z. Electrochemical Energy Storage Material – Li (Beijing Institute of Nanoenergy and K. Unal (Chemistry Department, Supercapacitors and High Power Density Koc University, Koc University Surface Electrochemical Thermocell. Chen (College of Chemistry, Nankai University) 11:40 80 Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Molybdenum Sulphide and Molybdenum Sulphide/Oxide 16:40 89 Sputtered Iridium Oxide Nanocomposite As Active Materials for Microsupercapacitors Operating in Supercapacitor Electrode – C. Hong (Mechanical Engineering, (The University of Texas at Dallas) Sungkyukwan University), and T. Pala (Indian Institute of State Hybrid Supercapacitors on Fabric Technology Kanpur), and S. Sabolsky Electrodeposition As High Performance Electrode Material for Supercapacitor Applications – G. Schnabel (National Lithium Ion Anodes 3 – 08:00 – 12:00 Renewable Energy Laboratory), G. Lone Star A1, Dallas Sheraton Convention Center Patwardhan (The University of Shefeld) 08:20 296 Electrochemical Properties of Amorphous Lithium Ion Cathodes 1 – 08:00 – 12:20 Silica As an Anode Material for Li-Ion Chair(s): Yiman Zhang and Xinhua Liang Batteries – V. Vullum-Bruer (Norwegian 08:00 306 Surface Modifcation for Suppressing University of Science and Technology) Interfacial Parasitic Reactions of Nickel-Rich 08:40 297 Tunable Syntheses of Advanced Silicon Lithium-Ion Cathode – J. Chen (Argonne National Laboratory) 09:20 299 Nanocarbon Composites for Energy Storage Applications – L. Ci (Shandong University) 08:20 307 Redox Chemistry in Conventional Layered Lithium Metal Oxide Cathodes – W. Sallis (Lawrence Berkeley 10:00 300 Silicon Nano Wires Anodes for High National Laboratory), B. Lutkenhaus (Texas A&M University) to Accommodate the Fast Charging for 10:40 302 Alleviate Gassing Problem of Li4Ti5O12 Lithium Secondary Batteries – B. Wang (National Kim (Dong-A University) Taiwan University of Science and Technology), 09:20 310 A Discovery of an Unexpected Metal H. Wu (Industrial Technology Research Dissolution of Thin-Coated Cathode Institute), and N. Wu (National Taiwan Particles: Its Theoretical and Experimental University) Explanations – Y. He (Missouri University of 11:00 303 Light-Weight and Flexible Carbon Science and Technology), S. Wang (Florida International O2: Preserving Cathode Structure for Long University) Term Cycling (1000 Cycles) Li-Ion Batteries – H. Battery Model Coupling Macroscopic Li (National Renewable Energy laboratory), and Microscopic Deformations – W. Colclasure (National Energy Laboratory) Renewable Energy Laboratory) 11:00 314 Structural and Electrochemical 16:00 325 Pre-Electrochemical Treatment Efect Characterization of Thin Film Li2MoO3 of Cu Eqcm Electrode on Lithium Cathodes – E. Nishihara (Ochanomizu University) Nanda (Oak Ridge National Laboratory) 16:20 326 Graphene Pliable Pockets Remedying 11:20 315 A Comparison of Electrode Surface Films Nanocrystalline Metal Anode for All Li Formed with Diferent Oxide Cathodes Ion Types Energy Storages Induced By for Lithium-Ion Batteries – E. Erickson Polymer-Triggered Synthesis Process in an (The University of Texas at Austin, Bar-Ilan Expeditious, Scalable and Inexpensive Way University), W. Kang (Korea Advanced University of Texas at Austin) Institute of Science and Technology) 11:40 316 Structure and Electrochemistry of LiV3O8 16:40 327 Morphology Controlled Fabrication of Thin Film Electrode: Efect of Difusion Rate Nanostructured Molybdenum Oxides By and Concentration on Cell Polarization – Y. Monoxide Electrodes during Initial Cycle in Dudney (Oak Ridge National Laboratory) Lithium-Ion Batteries – D. Lee (City University of Hong Kong) Transition Metal Oxide Cathode Electrode – 17:20 329 Efect of Diferent Carbon Precursors on J.

10 mg maxalt visa. Body in Pain: Treatment (2 of 3).

References

- Alboni P, Botto GL, Baldi N, et al. Outpatient treatment of recent-onset atrial fibrillation with the 'pill-in-the-pocket' approach. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2384-2391.

- Hou J, Renigunta A, Konrad M, et al: Claudin-16 and claudin-19 interact and form a cation-selective tight junction complex, J Clin Invest 118:619n628, 2008.

- Baron TH, DeSimio TM. New ex-vivo porcine model for endoscopic ultrasound-guided training in transmural puncture and drainage of pancreatic cysts and fluid collections (with videos). Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:34-39.

- Buck, L., Michalek, J., Van Sickle, K., et al. Can gastric irrigation prevent infection during NOTES mesh placement? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008; 12(11):2010-2014.

- Herr HW: Should antibiotics be given prior to outpatient cystoscopy? A plea to urologists to practice antibiotic stewardship, Eur Urol 65(4):839n842, 2014.