Jonathan Mark Zenilman, M.D.

- Chief, Division of Infection Diseases, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center

- Professor of Medicine

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/profiles/results/directory/profile/0005115/jonathan-zenilman

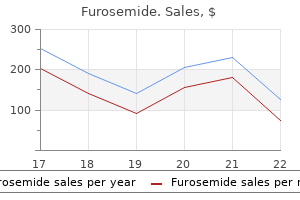

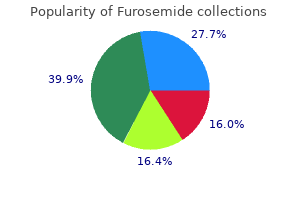

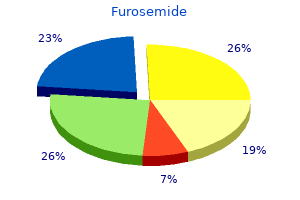

Tanaka M blood pressure 220 120 buy furosemide 100mg on line, Chari S 01 heart attackm4a generic 40mg furosemide overnight delivery, Adsay V, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Falconi M, Shimizu M, et al; International Association of Pancreatology. Solid-Cystic (Papillary-Cystic) Tumor Solid-cystic tumor, which has various names, has a striking female predominance and usually occurs in adolescence. The histogenesis is unclear, but histologically, pseudopapillary and microcystic changes are seen. The prognosis is good, and most of the tumors can be considered benign, but occasionally metastatic disease occurs. The prevalence of gallstones varies widely and is as high as 60% to 70% among American Indians and as low as 10% to 15% among white adults of developed countries. The prevalence is less among black Americans, East Asians, and people from sub-Saharan Africa. In the United States, gallstone disease is one of the most common and costly digestive diseases that requires hospitalization. It is newly diagnosed in more than 1 million people annually, and approximately 700,000 cholecystectomies are performed each year. Therefore, an understanding of the anatomy and physiology, clinical presentation, and efficient approaches to investigations and management of gallstone disease are important. Anatomy and Physiology Gallbladder and Cystic Duct Anatomy the gallbladder is a piriform sac situated primarily in the cystic fossa on the posteroinferior aspect of the right hepatic lobe. The neck of the gallbladder is connected to the cystic duct, which is 3 to 4 cm long, eventually joining the common hepatic duct to form the common bile duct. The cystic artery, usually a branch from the right hepatic artery, courses superior to the cystic duct and reaches the superior aspect of the neck, where it divides into superficial and deep branches. Anatomical variations include gallbladder agenesis, multiple gallbladders, bilobed gallbladder, and double cystic duct. A phrygian cap is an inconsequential deformity reflecting kinking of the gallbladder fossa and is usually noted with radionuclide hepatobiliary imaging. In double gallbladder, each gallbladder may have its own cystic duct, or the duct may join to form a common cystic duct before joining the common hepatic duct. The organic solutes include miscellaneous proteins, bilirubin, bile acids, and biliary lipids. Bilirubin is a degradation product of heme and usually is present as conjugated water-soluble diglucuronide. The unconjugated form of bilirubin precipitates, contributing to pigment or mixed cholesterol stones. Pancreas and Biliary Tree capable of solubilizing hydrophobic lipid molecules in bile or intestinal chyme. The primary bile acids (cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid) are manufactured in the liver. They are converted to secondary bile acids (deoxycholic and lithocholic acids) by bacteria in the gut. The major biliary lipids, cholesterol and lecithin (phospholipid), are insoluble in water. They are secreted into bile as lipid vesicles and are carried in both vesicles and mixed micelles. In health, the gallbladder concentrates bile 10-fold for efficient storage during fasting and empties 25% of its contents every 2 hours. Intraduodenal protein and fat release cholecystokinin, which stimulates contraction of the gallbladder, relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi, and flow of bile to the intestine. Gallstone Pathogenesis and Epidemiology Gallstones are categorized on the basis of composition as cholesterol gallstones (80% of patients) and pigment (black and brown) gallstones (20%). Each category has a unique structural, epidemiologic, and risk factor profile (Table 39. Cholesterol crystal formation requires the presence of 1 or more of the following: cholesterol supersaturation, accelerated nucleation, or gallbladder hypomotility, bile stasis, and genetic factors. Cholesterol gallstones contain a mixture of cholesterol (50%99% by weight), a glycoprotein matrix, and small amounts of calcium and bilirubin. Cholesterol supersaturation can result from deficient secretion of bile acid or hypersecretion of cholesterol. Bile acid secretion may be diminished because of decreased synthesis, as occurs with older age or liver disease, or because of decreased enterohepatic circulation, as occurs with motor disorders, hormonal defects, and increased gastrointestinal losses from bile acid sequestrant therapy or terminal ileal disease, resection, or bypass. Cholesterol secretion increases with hormonal stimuli (female sex, pregnancy, exogenous estrogens, and progestins), obesity, hyperlipidemia, age, chronic liver disease, and sometimes with excessive dietary polyunsaturated fats or increased caloric intake. Gallbladder dysmotility results in inadequate clearance of crystals and nascent stones. Motility is decreased in the presence of supersaturated bile even before stone formation. Decreased motility is a dominant contributing factor to stone development during pregnancy, prolonged total parenteral nutrition, somatostatin therapy, or somatostatinoma. They are rare in populations of Africa and most of Asia, they are common in most Western populations (15%-20% of women, 5%-10% of men), and they occur almost uniformly in North and South American Indians (70%-90% of Systemic circulation Synthesis (0. Ileal absorption returns 97% of intraluminal bile acids to the circulation; 90% of bile acids are extracted from the portal system on their first pass through the liver. Studies have shown that interactions of 5 defects result in nucleation and crystallization of cholesterol monohydrate crystals in bile, with eventual formation of gallstones. For all populations, the prevalence increases with age and is approximately twice as high in women as in men. Generally, pigment gallstones are formed by the precipitation of bilirubin in bile. Black pigment gallstones are formed in sterile gallbladder bile in association with chronic hemolytic states, cirrhosis, Gilbert syndrome, or cystic fibrosis, or they may have no identifiable cause. These stones are small, irregular, dense, and insoluble aggregates or polymers of calcium bilirubinate. Brown pigment gallstones occur primarily in the bile ducts, where they are related to stasis and chronic bacterial colonization, as may occur above strictures or duodenal diverticula, following sphincterotomy, or in association with biliary parasites. They are softer than black pigment gallstones and may soften or disaggregate with cholesterol solvents. Clinical Presentation and Complications Cholelithiasis Frequently, the diagnosis of asymptomatic cholelithiasis is the result of widespread use of abdominal ultrasonography to evaluate nonspecific abdominal symptoms. Approximately 10% to 20% of Western populations have cholelithiasis, and of these people, 50% to 70% are asymptomatic when cholelithiasis is initially identified. Commonly, asymptomatic disease has a benign course and the proportion of those with disease that evolves from asymptomatic to symptomatic is relatively low (10%-25%). When patients with gallstones eventually become symptomatic, only 2% to 3% present initially with acute cholecystitis or other complications. Prophylactic cholecystectomy should be considered, however, for patients who are planning extensive travel in remote areas and for American Indian populations, in whom the relative risk for stone-associated gallbladder carcinoma is 20 times higher than for those without stones. Patients with midgut carcinoid tumors are commonly treated with somatostatin analogues. The adverse effects of these analogues include impairment of gallbladder function, formation of gallstones, and cholecystitis. Therefore, prophylactic cholecystectomy may be beneficial for this cohort of patients. Concomitant cholecystectomy at the time of a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for ultrasound-confirmed gallbladder pathology is feasible and safe and may reduce the potential for future gallbladder-related morbidity. A similar rationale may be used when prophylactic splenectomy is performed in patients with hereditary spherocytosis. Cholecystectomy is not recommended for asymptomatic patients who have stones and diabetes mellitus or sickle cell disease if they have access to medical care. Progressive gallstone dissolution by oral litholysis with hydrophilic ursodiol may be attempted in patients who have mild symptoms and small, uncalcified cholesterol gallstones in a functioning gallbladder with a patent cystic duct. Daily ursodiol may reduce the frequency of gallstone formation in obese patients eating low-calorie diets. Biliary colic is a relatively specific form of pain secondary to increased intragallbladder pressure due to hormonal or neural stimulation. This may be triggered by a fatty meal or a stone compressed against the gallbladder outlet or cystic duct opening.

Ingested proteins are cleaved initially by pepsin (an endopeptidase) blood pressure medication interactions cheap 100mg furosemide with amex, which is produced from the precursor pepsinogen in response to a gastric pH between 1 and 3 heart attack 1d lyrics 40 mg furosemide free shipping, with inactivation at a pH greater than 5. When gastric chyme reaches the small intestine, enterokinase from duodenal enterocytes activates trypsin. Trypsin then converts pancreatic proteases from inactive to active forms in a cascade fashion, subsequently cleaving proteins into various amino acids and small peptides. Additional mucosal brush border oligopeptidases further cleave small peptides, with free amino acids and oligopeptides crossing into the cytoplasm either freely or through carrier-mediated channels, some of which are sodium-mediated channels. In addition to disorders that affect protein digestion and absorption, there can be significant loss of protein from the intestinal tract; these conditions are referred to as protein-losing enteropathies. Although the liver can respond to protein loss by increasing the production of various proteins such as albumin, a protein-losing state develops when net loss exceeds net production. Three major categories of gastrointestinal-related disorders are associated with excess protein loss: 1) diseases with increased mucosal permeability without erosions, 2) diseases with mucosal erosions, and 3) diseases with increased lymphatic pressure. The clinical features of a protein-losing enteropathy include diarrhea, edema, ascites, and possible concomitant carbohydrate and fat malabsorption, because isolated protein malabsorption or loss is infrequent. Laboratory studies may show a low serum level of protein, albumin, and immunoglobulins, except for IgE, which has a short half-life and rapid synthesis. If the protein-losing state is from lymphangiectasia (primary or acquired), patients may also have lymphocytopenia. To diagnose a protein-losing enteropathy, an 1-antitrypsin clearance test should be performed. This sequence avoids degradation of 1-antitrypsin by pepsin, since the elevated pH from acid suppression will inactivate pepsin and hence allow adequate assessment of gastric loss. Diarrhea the mechanism for diarrhea is often from a combination of decreased absorption (a villous function) and increased secretion (a crypt function). Diarrhea can be categorized in several ways: inflammatory versus noninflammatory and secretory versus osmotic. The clinical features of inflammatory diarrhea may include abdominal pain, fever, and tenesmus. Stools may be mucoid, bloody, smaller volume, and more frequent, unless the small bowel also is affected diffusely. However, if the inflammation is microscopic, these clinical and stool features may be absent (eg, microscopic colitis). Common causes of inflammatory diarrhea include invasive infections, inflammatory bowel disease, radiation enteropathy, and ischemia. Noninflammatory causes of diarrhea tend to produce watery diarrhea, without fever or gross blood, and the stool appears normal on microscopy. There are many causes, but infections, particularly by toxin-producing organisms, are common. Osmotic diarrhea is due to the ingestion of poorly absorbed cations, anions, sugars, or sugar alcohols (such as sorbitol or xylitol). These ingested ions obligate retention of water in the intestinal lumen to maintain osmolality equal to that of other body fluids (290 mOsm/kg); this subsequently causes diarrhea. Osmotic diarrhea can occur also from maldigestion or malabsorption (pancreatic insufficiency or disaccharidase deficiency). The stool osmotic gap is calculated by adding the stool sodium and potassium concentrations, multiplying by 2, and subtracting this amount from 290 mOsm/kg. A gap greater than 100 mOsm/kg strongly supports an osmotic cause for the diarrhea, whereas a gap less than 50 mOsm/kg supports a secretory cause. Small Bowel and Nutrition contamination and higher values indicating that the specimen was not processed readily. The utility of checking stool osmolality therefore lies in determining whether the stool specimen was processed properly. Stool volumes tend to be less with osmotic diarrhea than with secretory diarrhea, and the diarrhea tends to abate with fasting. For secretory diarrhea to occur, the primary bowel function converts from net absorption to net secretion. Normally, up to 9 to 10 L of intestinal fluid crosses the ligament of Treitz each day, and all but 1. The colon then absorbs all but 100 to 200 mL of the fluid, which is evacuated as stool. In secretory diarrhea, net absorption converts to net secretion, and the small bowel loses its normal capacity to absorb the large volume of fluid; thus, liters of fluid pass into the colon daily. Although the colon can adapt and absorb nearly 4 L of liquid from the stool each day, larger fluid loads cannot be absorbed, and this results in large-volume diarrhea, often liters per day. Dehydration can occur easily, and replacement fluids need to contain adequate concentrations of both sodium and glucose, as in oral rehydration solutions, to maximize small-bowel absorption of sodium and water. Consuming beverages that have low sodium concentrations (water, sports drinks, or juices) may actually worsen the volume status of the patient because sodium will be secreted into the bowel lumen to maintain an isosmotic state, with water following the stool sodium loss. Characteristics, common causes, and testing strategies for secretory and osmotic diarrhea are listed in Table 8. Intestinal Resections and Short Bowel Diarrhea and malabsorption can result from any process that shortens the length of the functioning small bowel, whether from surgery or from relative shortening caused by underlying disease. Whether diarrhea and malabsorption occur with a shortened small bowel depends on several factors: the length of bowel resected, the location of the bowel resected, the integrity of the remaining bowel, and the presence of the colon. The length and location of the resected small bowel affect the enterohepatic circulation of bile. If less than 100 cm of distal ileum is resected, the liver can compensate for the loss of absorptive capacity by producing an increased amount of bile salts, which enter the colon and cause a bile-irritant secretory diarrhea. This diarrhea is treated with cholestyramine, which binds the excess bile salts and improves diarrhea. If more than 100 cm of distal small bowel is resected, including the terminal ileum, the liver can no longer compensate for the loss of absorptive capacity. The resulting bile salt deficiency leads to steatorrhea since micelle production is negatively affected and long-chain triglycerides cannot be effectively handled. This can be managed by prescribing a diet that consists of medium-chain triglycerides, which do not require bile salts or micelle formation for absorption because they are absorbed directly into the portal blood. The terminal ileum has the specialized function of absorbing and recirculating bile salts and binding the cobalamin-intrinsic factor complex. However, the opposite is not true; the jejunum is not able to compensate for the loss of the Table 8. Malabsorptive Disorders, Small-Bowel Diseases, and Bacterial Overgrowth 93 specialized functions of the ileum. Normally, in the small bowel, calcium binds to oxalate, and this complex passes into the colon and is excreted in the stool. With a shortened small bowel and absence of the colon, calcium preferentially binds to the fatty acids in the stool, leaving oxalate unbound. In the case of a shortened small bowel and intact colon, calcium again binds to the fatty acids, and the free or unbound oxalate is absorbed from the colon, leading to the formation of calcium oxalate kidney stones. Although the absolute length of small bowel that is resected is important, the integrity of the remaining bowel is crucial because diffuse pathologic processes such as Crohn disease or radiation enteritis can result in a functionally shortened bowel without surgical resection. Whether a patient has an intact colon is of considerable importance if there has been prior small-bowel resection. The colon can adapt by increasing water and sodium absorption, by acting as an intestinal "brake" to slow motility, and by salvaging nonabsorbed carbohydrates to provide additional calories for patients with short bowel syndrome. Patients who still have an intact colon may not need parenteral nutrition if they have 50 to 100 cm of small bowel remaining. However, patients who no longer have a colon may need parenteral nutrition when the length of the small bowel is less than 150 to 180 cm. In the early postoperative stage, hypersecretion of gastric acid inactivates pancreatic enzymes, leading to diarrhea and steatorrhea. Until the remaining small bowel has time to adapt, intestinal transit is rapid because of the loss of surface area. Early management of short bowel syndrome includes aggressive treatment with antidiarrheal agents, total parenteral nutrition, and gastric acid suppression. The prevalence is highest among persons of European descent, and the disease is being diagnosed with greater frequency in North America as clinicians become more familiar with the many manifestations of the disease.

An olfactory subsystem that detects carbon disulfide and mediates food-related social learning pulse pressure of 10 discount furosemide 40 mg on-line. Olfactory mechanisms of stereotyped behavior: On the scent of specialized circuits lower blood pressure quickly naturally order genuine furosemide on-line. Furthermore, phosphoinositide signaling may be important in other cell types within the olfactory epithelium. As will be seen below, phosphoinositides certainly play an important role in chemosensory transduction in another olfactory tissue, the vomeronasal organ (Ch. The vomeronasal organ is an accessory chemosensing system that plays a major role in the detection of semiochemicals this functional class of odorants, which includes both conspecific and interspecific cues, can convey important information such as social or mating status, genetic identity, food safety or the presence of disease. Most vomeronasal sensory neurons are narrowly tuned to specific chemical cues, and utilize a unique mechanism of sensory transduction Unfortunately, technical challenges have slowed progress towards pairing most vomeronasal receptors with their cognate ligands. V1R-expressing neurons respond largely to volatile stimuli, including several compounds found in rodent urine and that have been implicated as pheromones (odorants released by one member of a species that elicit a behavioral or hormonal response in another member). In contrast V2R-expressing neurons seem to be sensitive to peptide or protein stimuli found in urine or glandular secretions, including stimuli that can elicit mating behaviors in female conspecifics or fear of a predator. However, the activation of vomeronasal receptors has still not been directly linked to diacylglycerol production via any G protein or phospholipase isoforms. The chemical complexity of taste stimuli suggests that taste receptor cells utilize multiple molecular mechanisms to detect and distinguish among these compounds. Our sense of taste can detect and discriminate among various ionic stimuli-for example, Na as salty, H as sour, sugars as sweet and alkaloids as bitter. These nerves relay taste information both to brainstem taste areas and to circuits involved in oromotor reflexes. The taste buds are embedded within the nonsensory lingual epithelium of the tongue and are housed within connective tissue specializations called fungiform, foliate and circumvallate papillae. The taste bud is a polarized structure with a narrow apical opening, termed the taste pore, and basolateral synapses with afferent nerve fibers. However, significant progress has been made in identifying key players in the transduction of sweet, umami and bitter taste. Subsequently, several groups utilized a combination of molecular biological and genetic approaches to identify the gene encoding a third family member, T1R3 (Vigues et al. Certain mutations in the mouse Tas1r3 gene (which encodes T1R3) correlate with a reduced sensitivity to sweet compounds, including saccharin and many natural sugars. The identification of Tas1r3 as the saccharin-sensitivity gene Sac provided the first evidence that the T1Rs might be involved in sweet taste. The T1Rs function as heteromeric receptors (likely dimers), with T1R2 and T1R3 combining to form a receptor for sweettasting compounds including sugars, sweeteners, and some D-amino acids (Li et al. In contrast, T1R1/T1R3 heteromers are insensitive to sweet-tasting stimuli but do respond to umami stimuli, including some L-amino acids (Li et al. Furthermore, T1R1/ T1R3 responses are potentiated by 5-ribonucleotides, a characteristic of umami taste. This overlapping pattern of expression is consistent with bitter taste behavior, as animals do a poor job of discriminating bitter compounds and may be more dependent on high taste sensitivity to these compounds, which are often toxic. For example both receptor types are expressed in enteroendocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract, where it appears they sense ingested nutrients, metabolites or other factors present in the gut lumen and they influence hormonal responses and/or nutrient assimilation. Therefore, while both receptor families certainly play critical roles in taste, it may be too simplistic to refer to them as "taste" receptors. Type 2 Taste Receptors (T2Rs) Mediate Responses to Bitter-Tasting Stimuli A distinct receptor family is involved in the detection of bitter tastants. Bitter agents are structurally diverse, suggesting a multiplicity of receptors and/or detection pathways. Many bitter compounds are lipophilic and membrane permeant, and may act on intracellular or integral membrane targets. Most human T2Rs, as well as many rodent homologues, have been paired to one or more bitter-tasting ligands, confirming the role of T2Rs in bitter taste. The first heterotrimeric G protein subunit to be implicated in this process was -gustducin (McLaughlin et al. These animals do retain some residual responses to these stimuli, suggesting a role for other G protein isoforms. These interesting results suggested that different groups of taste cells are dedicated to encoding individual taste qualities, a model born out by subsequent experiments (Chandrashekar et al. Many textbooks continue to incorrectly state that taste sensitivities are strictly localized on the gustatory epithelium. However, there is some regionalization of sensitivity that is consistent with the observation that taste receptors and intracellular signaling components are differentially localized across the gustatory epithelium. These differential patterns of expression highlight the functional and molecular complexity of taste transduction and the challenges in understanding the subtleties of diverse signaling cascades in the gustatory system. In contrast, the molecular mechanisms underlying general salt taste remain unclear, although candidates have been proposed. Sour taste is a function of the acidity of a solution, depending primarily on the proton concentration and to a lesser extent on the particular anion involved. Several mechanisms have been proposed to mediate sour taste, including proton or pH-dependent gating of ion channels, direct flux of protons through ion channels or intracellular acidification of ion channels or other proteins. General anosmia caused by a targeted disruption of the mouse olfactory cyclic nucleotidegated cation channel. A zonal organization of odorant receptor gene expression in the olfactory epithelium. Information coding in the olfactory system: Evidence for a stereotyped and highly organized epitope map in the olfactory bulb. Formyl peptide receptor-like proteins are a novel family of vomeronasal chemosensors. Spatial segregation of odorant receptor expression in the mammalian olfactory epithelium. Different evolutionary processes shaped the mouse and human olfactory receptor gene families. Coding of sweet, bitter, and umami tastes: Different receptor cells sharing similar signaling pathways. The senses of hearing, balance, and touch all rely on mechanoreceptors, as do the proprioceptive sensations that tell an organism how it is situated within the environment. Mechanoreception is probably one of the most ancient of the senses, with mechanosensitivity existing in virtually every type of organism in all three domains-Bacteria, Archaea and Eukarya (Kloda & Martinac, 2002). Models for mechanotransduction allow comparison of mechanoreceptors from many organisms and cell types Mechanoreceptors use ion channels for transducing sensory information. Because the currency of the nervous system is the membrane potential, by opening an ion channel a cell can quickly and extensively modulate its membrane potential and hence impact neurotransmitter release, the final step in mechanoreception at the cellular level. Ion channels open or close upon relative movement of internal domains, which can be elicited by voltage, ligand binding or force. A key question in the study of mechanotransduction is how force can influence domain movements within ion channels. Multiple models of how this could occur have been generated from the study of mechanosensitive ion channels in bacteria and other cell types. These mechanotransduction models have allowed comparison of the multiple types of mechanoreceptors that exist within different species. In one model, ion channel domains are moved by tension within the plasma membrane. Bacterial osmosensors are thought to work this way; as membrane tension increases, the channels gate to reduce tension (Sukharev & Cori, 2004).

The toxin is folded into three -helices with two -strands and it is both stabilized and activated by Ca2 pulse pressure 95 order furosemide 100 mg without a prescription. The activity of the toxin is much higher against membrane-inserted phospholipids than against isolated ones due to the higher efficiency of interfacial catalysis 5 order generic furosemide canada, which depends on the absorption of the enzyme onto the lipid-water interface, facilitating the seamless diffusion of the phospholipid molecule from the membrane to the active site channel. Some 100 -neurotoxins have been isolated, the most used being -bungarotoxin, synthesized by the Asian krait Bungarus multicinctus. Exposure of humans to low doses of toxin that induce partial blockade of junctional receptors can produce weakness and fatigability that resemble acquired myasthenia gravis. Higher doses can lead to complete neuromuscular block, paralysis, respiratory failure and death. The -toxins responsible for the postsynaptic curarimimetic activity are proteins of 7 to 8 kDa. Structurally, they fall into two groups: long toxins, which are comprised of 71 to 74 amino acids and five internal disulfide bonds, and short toxins, with 60 to 62 amino acids and four internal disulfide bonds. All -toxins exhibit a high degree of homology and are shaped as concave disks with a small projection at one end. The reactive site of the protein is on the concave surface and involves the regions encompassed by residues 32 to 45 and 49 to 56 as well as isolated residues from other regions of the molecule. This family of toxins may have arisen through a process of gene duplication in the spider. Envenomation by spiders of the genus Latrodectus causes lactrodectism, a generalized poisoning syndrome that develops within an hour of being bitten, with pain first localized at regional lymph nodes. Rapidly, generalized muscle cramps and rigidity develop, together with hypertension and transient tachycardia followed by bradycardia, profuse sweating and oliguria. Stonefish stings cause a similar envenomation with prominent autonomic nervous system dysfunction. All of these symptoms can be ascribed to hyperexcitability of various nerve terminals. Trachynilysin, a toxin of ~150 kDa, has been isolated from the venom of the stonefish Synanceia trachynis, and similar-sized stonustoxin and verructoxin are synthesized by S. Exocytosis of synaptic vesicles takes place at active zones and is followed by unaltered vesicular recycling. In addition, neurexin Ia and a 120-kDa integral membrane protein associated with the G protein -subunit (see Ch. Other fish toxins are yet to be characterized, but it appears that all fish venoms act both pre- and post-junctionally to cause depolarization and that the venoms possess cytolytic activity. In contrast, venoms produced by the marine predatory snails of the genus Conus are significantly more diverse, the total number of peptides in the venom of a single Conus species ranging from 50 to 200. About 50,000 different Conus peptide toxins are estimated to exist, owing to a synthetic strategy that amounts to a combinatorial library scheme (Terlau & Olivera, 2004). The most prominent venoms belong to the conotoxin type, a class of peptides containing multiple disulfide bonds usually targeted against ion channels. Electrolyte imbalances alter the voltage sensitivity of muscle ion channels While the effect of changing ionic concentrations across cellular membranes on membrane potential and excitability is dictated by the Nernst equation (see Chapter 4), plasmatic electrolyte disturbances affect excitable tissues differently depending on the rate of exchange of the extracellular solution and the mobility of ions across the often narrow intercellular spaces (Jones et al. Hypercalcemia causes divalent metal ionic screening of membrane surface charges and is associated with weakness and fatigability due to muscle dysfunction caused by offsetting of the extracellular potential to which the voltage sensors of all ion channels are exposed, and which can eventually lead to chronic myopathy. Effects on the brain include altered consciousness ranging from apathy to agitation and seizures. Common causes of hypercalcemia are hyperparathyroidism, metastatic disease and vitamin D intoxication. Hypocalcemia, a feature of hypoparathyroidism, malabsorption, vitamin D deficiency and-rarely-of thyroid and parathyroid surgery, initially causes numbness of mouth, hands and feet, followed by tetany or spasms in the same distribution. The encephalopathy associated with hypocalcemia is more dramatic, with hallucinations, psychosis and seizures. Effects remote from the cerebral cortex include parkinsonism and chorea (see Chapter 49) and even spinal cord dysfunction. The effects of magnesium electrolyte imbalance resemble those of calcium, except that hypomagnesemia may escape analytical detection because magnesium is predominantly an intracellular ion. Renal tubular acidosis may cause hypomagnesemia, while renal failure commonly causes hypermagnesemia. Alterations in potassium concentration are worse tolerated, owing to the fundamental role of potassium in setting resting membrane potential in almost all excitable cells of the organism. Hyperkalemia usually causes cardiac arrhythmia before nerve and muscle dysfunction. The latter abnormalities are manifested as weakness preceded by burning sensation (paresthesia) and are sometimes accompanied by mental changes. Hypokalemia, on the contrary, causes primarily neuromuscular disturbance, with fatigability, weakness of large (proximal) muscles and, ultimately, lysis of the muscle membrane (rhabdomyolysis with release of myoglobin to the plasma). The neuromuscular junction and muscle are more resistant to changes in sodium concentration, to which they are minimally permeable at rest. In fact, the consequences of sodium disturbance relate instead to the role of this ion in maintaining the osmotic equilibrium between the brain and plasma and range from depression of consciousness, coma and seizures caused by hyponatremia, to brain shrinkage and tearing of superficial blood vessels due to excessive serum osmolarity due to hypernatremia. Rapsyn carboxyl terminal domains mediate muscle specific kinase-induced phosphorylation of the muscle acetylcholine receptor. Muscle-specific receptor tyrosine kinase endocytosis in acetylcholine receptor clustering in response to agrin. Identification and characterization of the high affinity [3H]ryanodine receptor of the junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2 release channel. Toward a structural basis for the function of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and their cousins. State-dependent accessibility and electrostatic potential in the channel of the acetylcholine receptor. Threedimensional architecture of the calcium channel/foot structure of sarcoplasmic reticulum. Results of these studies are being used to design novel therapies to be tested in clinical trials in humans. The paralysis/muscle atrophy and spasticity are the result of degeneration of motor neurons in the spinal cord/ brain stem and motor cortex, respectively. The onset of this illness is typically in the fifth or sixth decade of life; affected individuals die usually within two to five years of appearance of symptoms. The pathological processes, which affect particularly the spinal and corticospinal motor neurons, appear to evolve through a series of stages influencing size, shape, content, metabolism and physiology of these cells. The investigations described below tested the hypothesis that this type of pathology was the result of defects in axonal transport. Moreover, it was hypothesized that impairments in transport could also be associated with a "dying-back" phenomenon. Moreover, as a part of the dying-back process and dissociation of neurons from their targets, retrogradely transported trophic support to neuronal cell bodies is compromised, which, in turn, affects the viability of these cells (Kolatsios et al. In the final stages, motor neurons exhibit several features of apoptosis, which are discussed below (Martin et al. Ultimately, the numbers of motor neurons in brainstem nuclei and spinal cord are reduced and there is a loss of large pyramidal neurons in motor cortex associated with secondary degeneration of the corticospinal tracts (Ince, 2000). The mechanisms of cell death, including apoptosis and necrosis, are the subjects of very active research discussed in Ch. Some investigations support the idea of an inappropriate reemergence of a programmed cell death mechanism involving p53 activation and cytosol-to-mitochondria redistributions of cell death proteins. This illness, which was originally described in a Tunisian kindred, is characterized by spasticity (involvement of upper motor neurons) and weakness/amyotrophy (involvement of lower motor neurons) (Hadano et al. This disease is manifested by distal weakness beginning at approximately 25 years of age, slow progression and a normal lifespan.

Cheap 40mg furosemide fast delivery. Healing Of High Blood Pressure Hyperthyroidism And Depression.

References

- Geradts J, Fong KM, Zimmerman PV, Minna JD. Loss of Fhit expression in non-small-cell lung cancer: correlation with molecular genetic abnormalities and clinicopathological features. Br J Cancer 2000;82:1191-7.

- Kimura W, Kuroda A, Morioka Y: Clinical pathology of endocrine tumors of the pancreas. Analysis of autopsy cases. Dig Dis Sci 36:933, 1991.

- Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991-4997.

- Frank S, Johnson A, Ross J Jr: Natural history of valvular aortic stenosis, Br Heart J 35:41-46, 1973.

- Hashmi JA, Baria AT, Baliki MN, et al. Brain networks predicting placebo analgesia in a clinical trial for chronic back pain. Pain. 2012; 153(12):2393-2402.

- Sainani NI, Catalano OA, Holalkere NS, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: current and novel imaging techniques. Radiographics. 2008;28(5):1263-1287.