Christina M. Davidson, MD

- Assistant Professor

- Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine

- Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Baylor College of Medicine

- Houston, Texas

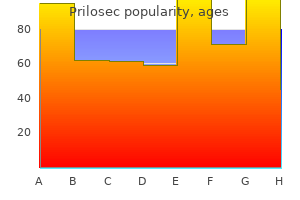

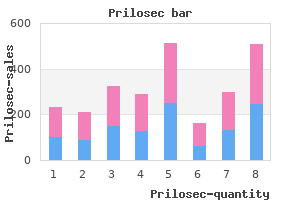

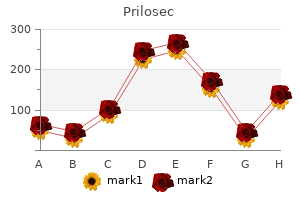

In addition www gastritis diet com order prilosec mastercard, a group of miscellaneous movement disorders-myoclonus gastritis diet блиц discount prilosec 20 mg visa, facial and cervical dyskinesias diet for gastritis and diverticulitis buy cheap prilosec line, focal limb dystonias, and tics-is described in this chapter. These disorders are largely involuntary in nature and can be quite disabling but they have an uncertain pathologic basis, as alluded to in Chap. Its rhythmic quality distinguishes tremor from other involuntary movements, and its oscillatory nature distinguishes it from myoclonus and asterixis. The following types of tremors, the clinical features of which are summ arized in. In clini cal analysis they are usually distinguishable on the basis of (1) relation to movement and posture, (2) frequency; (3) the pattern of activity of opposing (agonist-antagonist pairs) muscles, i. Such a classification also differenti ates tremors from a large array of nontremorous move ments, such as fasciculations, sensory ataxia, myoclonus, asterixis, epilepsia partialis continua, clonus, and rigor (shivering). Action Tremors Action tremors are evident during use of the affected body part, as opposed to tremor that is apparent in a position of rest or repose. Action tremors can be conve niently divided into two categories: goal directed action tremor of the ataxic type related to cerebellar disorders (discussed in Chap. A postural tremor occurs with the limbs and trunk actively maintained in certain positions (such as holding the arms outstretched) and may persist through out active movement. More particularly; the tremor is absent when the limbs are relaxed but becomes evident when the muscles are activated. The tremor is accentu ated as greater precision of movement is demanded, but it does not approach the degree of augmentation seen with cerebellar intention tremor. Most cases of action tremor are characterized by relatively rhythmic bursts of grouped motor neuron discharges that occur not quite synchro nously in opposing muscle groups as shown in. Slight inequalities in the strength and timing of contrac tion of opposing muscle groups account for the tremor. In contrast, rest (parkinsonian) tremor, is characterized by alternating activity in agonist and antagonist muscles. It is present in all contracting muscle groups and persists throughout the waking state and even in certain phases of sleep. The movement is so fine that it can barely be seen by the naked eye, and then only if the fingers are firmly outstretched; in most instances special instruments are required for its detection though asking the patient to aim a laser pointer at a distant target will often expose it. It ranges in frequency between 8 and 13 Hz, the dominant rate being 10 Hz in adulthood and somewhat less in childhood and old age. Several hypoth eses have been proposed to explain physiologic tremor, a traditional one being that it reflects the passive vibra tion of body tissues produced by mechanical activity of cardiac origin, but this cannot be the whole explanation. As Marsden has pointed out, several additional factors such as spindle input, the unfused grouped firing rates of motor neurons, and the natural resonating frequen cies and inertia of the muscles and other structures are probably of greater importance. Such a tremor, best elicited by holding the arms outstretched with fingers spread apart, is characteristic of intense fright and anxiety (hyperadrenergic states), certain metabolic disturbances (hyperthyroidism, hypercortisolism, hypo glycemia), pheochromocytoma, intense physical exertion, withdrawal from alcohol and other sedative drugs, and the toxic effects of several drugs-lithium, nicotinic acid, xanthines (coffee, tea, aminophylline), cocaine, methyl phenidate, other stimulant drugs and corticosteroids. Young and colleagues have determined that the enhance ment of physiologic tremor that occurs in metabolic and toxic states is not a function of the central nervous system but is instead a consequence of stimulation of muscular beta-adrenergic receptors by increased levels of circulat ing catecholarnines. A special type of postural action tremor, closely related to the enhanced physiologic tremor, occurs as the most prominent feature of the early stages of alcohol withdrawal. Withdrawal of other sedative drugs (benzo diazepines, barbiturates) following a sustained period of use produces much the same effect. Either of these may occur as the individual emerges from a relatively short period of intoxication ("morning shakes"). The mechanisms involved in alcohol withdrawal symptoms are discussed further in Chap. Aside from its rate the identifying feature is its appearance or marked enhancement with attempts to maintain a static limb posture. Like most tremors, essential tremor is worsened by emotion, exer cise, and fatigue. One infrequent type of essential tremor is faster than the usual essential tremor and of the same frequency (6 to 8 Hz) as enhanced physiologic tremor. Eventually, all tasks that require manual dexter ity become difficult or impossible. Typical essential tremor very often occurs in several members of a family, for which reason it has been called familial or hereditary essential tremor. The idiopathic and familial types canno t be distinguished on the basis of their physiologic and pharmacologic proper ties and probably should not be considered as separate entities. This condition has been referred to as "benign essential tremor," but this is hardly so in many patients in whom it worsens with age and greatly interferes with normal activities. Essential tremor most often makes its appearance late in the second decade, but it may begin in childhood and then persist. It is a relatively common disorder, with an esti mated prevalence of 415 per 1 00,000 persons older than the age of 40 years (Haerer et al). As described by Elble, the tremor frequency diminishes slightly with age while its amplitude increases. The tremor practically always begins in the arms and is usually almost symmetrical; in approximately 15 percent of patients, however, it may appear first in the dominant hand. A severe isolated arm or leg tremor should suggest another disease (Parkinson disease or focal dystonia, as described further on). In certain cases of essential tremor, there is involvement of the jaw, lips, tongue, and larynx, the latter imparting a severe quaver to the voice (voice tremor). The head tremor is also postural in nature and disappears when the head is supported. It has also been noted that the limb and head tremors tend to be muted when the patient walks. In some of our patients whose tremor remained isolated to the head for a decade or more, there has been little if any progression to the arms and almost no increase of the amplitude of movement. In the large series of familial tremor cases by Bain and colleagues, solitary jaw or head tremor was not found but we have observed isolated head tremor, as noted. Most patients with essential tremor will have identified the amplifying effects of anxiety and the ame liorating effects of alcohol on their tremor. We have also observed the tremor to become greatly exaggerated dur ing emergence from anesthesia in a few patients. Electromyographic studies reveal that the tremor is generated by more or less rhythmic and almost simultaneous bursts of activity in pairs of agonist and antagonist muscles. Less often, especially in the tremors at the lower range of frequency; the activity in agonist and antagonist muscles alternates ("alternate beat tremor"), a feature more characteristic of Parkinson disease, which the tremor then superficially resembles (see below). Tremor of either pattern may be disabling, but the less common, slower, alternate-beat tremor tends to be of higher amplitude, is more of a handicap, and is usually more resistant to treatment. Of more therapeutic interest, essential tremor is inhibited by the beta-adrenergic antagonist propranolol (between 80 and 200 mg per day in divided doses or as a sustained-release preparation) taken orally over a long period of time. The benefit is variable and often incomplete; most studies indicate that 50 to 70 percent of patients have some symptomatic relief but may complain of side effects such as fatigue, erectile dysfunction, and bronchospasm. The mechanism and site of action of beta-blocking agents is not known with certainty. It is blockade of the beta-2 adrenergic receptor that most closely aligned with reduction of the tremor. Several but not all of the other beta-blocking drugs are similarly effective to propranolol; metoprolol and nadolol, which are better tolerated than propranolol, are the ones most extensively studied, but they have yielded less consistent results than propranolol. The relative merits of different drugs in this class are discussed by Louis and by Koller et al (2000). Young and associates have shown that neither propranolol nor etha nol, when injected intraarterially into a limb, decreases the amplitude of essential tremor. These findings, and the delay in action of medications, suggest that their therapeutic effect is due less to blockade of the peripheral beta-adrenergic receptors than to their action on struc tures within the central nervous system. This is in con trast to the earlier mentioned muscle receptor-mediated effect of adrenergic compounds in physiologic tremor. It is possible that this ambiguity regarding the action of beta-blocking drugs is the result of their effect on physi ological tremor that is superimposed on essential tremor. The barbiturate drug primidone has also been effec tive in controlling essential tremor and may be tried in patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate beta-blocking medications, but many patients cannot tolerate the side effects of drowsiness, nausea, and slight ataxia. Treatment should be initiated at 25 mg per day and increased slowly to 75 mg per day in order to mini mize these effects. Gabapentin, topiramate (see Connor), mirtazipine, a variety of benzodiazepines and a large number of other drugs have been used with variable suc cess, but at the moment should probably be considered second-line therapies; these alternatives are discussed by Louis. The alternate-beat, slow, high-amplitude, kinetic-pre dominant type of essential tremor is more difficult to sup press but has reportedly responded to clonazepam (Biary and Koller); in our experience, however, this approach has not been as successful. Alcohol and primidone have also had less effect than they do in typical essential tremor. Indeed, the tremor has often been resistant to most attempts at suppression, for which reason surgical approaches are now being used (see further on). Injections of botulinum toxin into a portion of a limb can reduce the severity of essential tremor locally; but the accompanying weakness of arm and hand muscles often proves unacceptable to the patient. The same medica tion injected into the vocal cords can suppress severe voice tremor as described in a series of cases by Adler and colleagues as well as by others, but caution must be exercised to avoid paralyzing the cords. Doses as low as 1 U of toxin injected into each cord may be effective, with a latency of several days. The long-term repeated use of this treatment has not been adequately studied for essential-type limb or voice tremor. In resistant cases of essential tremor of the fast or slow variety, stimulation by electrodes implanted in the ventral medial nucleus thalamus or the internal segment of the globus pallidus (of the same type used to treat Parkinson disease) has produced a durable response over many years; details can be found in the small study reported by Sydow and colleagues. Tremor of Polyneuropathy Adams and coworkers described a disabling action tremor in patients with chronic demyelinating and paraprotein ernie polyneuropathies. When the legs are affected, the tremor takes the form of a flexion-extension movement of the foot, sometimes the knee. In the j aw and lips, it is seen as up-and-down and pursing movements, respec tively. The eyelids, if they are closed lightly, tend to flut ter rhythmically (blepharoclonus), and the tongue, when protruded, may move in and out of the mouth at about the same tempo as the tremor elsewhere.

With postural instability of any type there is a delay or inadequacy of corrective actions gastritis diet salad generic prilosec 20mg with amex. If all these tests can be successfully executed gastritis diet хошин order cheap prilosec on line, it may be assumed that any difficulty in loco motion is not because of impairment of a proprioceptive gastritis symptoms heartburn prilosec 20mg low price, labyrinthine-vestibular, basal ganglionic, or cerebellar mechanism. The following types of abnormal gait (Table 7-1) are so distinctive that, with practice, they can be recognized at a glance and interpreted correctly. Cerebellar Gait the main features are a wide base (separation of legs), unsteadiness, irregularity of steps, and lateral veering. Steps are uncertain, some are shorter and others longer than intended, and the patient may compensate for these abnormalities by shortening his steps or even keeping both feet on the ground simultaneously, which creates the as appearance of shuffling. Cerebellar gait is often referred to "reeling" or "drunken," but these terms are not correct and are characteristic instead of intoxication and of certain types of labyrinthine disease, as explained further on. With cerebellar ataxia, the unsteadiness and irregular swaying of the trunk are prominent when the patient arises from a chair or turns suddenly while walking and may be most evident when he has to stop walking abruptly and sit down; it may be necessary to grasp the chair for support. Cerebellar ataxia may be so severe that the patient cannot sit without swaying or assistance. In its mildest form, the ataxia is best demon strated only by having the patient walk a line heel to toe; after a step or two, he loses his balance and finds it neces together and eyes open will sway somewhat more with eyes closed. This slight increase in swaying may lead misat sary to place one foot to the side to avoid falling. As already emphasized, the patient with cerebellar ataxia who sways perceptibly when standing with feet tribution to a cerebellar sign of what is simply loss of pro prioceptive input to the cerebellum. Thus, the defect in cerebellar disease is primarily in the coordination of the sensory input from proprio ceptive, labyrinthine, and visual information with reflex movements, particularly those that are required to make rapid adjustments to changes in posture and position. This integrative deficiency is also reflected in the step ping test, in which the patient is asked to march on the spot with eyes closed as already mentioned. Those with vestibular and sometimes unilateral cerebellar disease have difficulty remaining stable and have a tendency to turn to the left or right or to move forward (occasionally backward) after 5 or 10 steps. Cerebellar abnormalities of stance and gait are usu ally accompanied by signs of cerebellar incoordination of the legs, but they need not be. The presence of the latter signs depends on involvement of the cerebellar hemi spheres as distinct from the anterosuperior (vermian) midline structures that dominate in the control of gait as described in Chap. Whatever the location of the lesion, its effect is to deprive the patient of knowledge of the position of his limbs and, more relevant to gait, to interfere with a large amount of afferent proprioceptive and related infor mation that does not attain conscious perception. A sense of imbalance is usually present but these patients do not describe dizziness. They are aware that the trouble is in the legs and not in the head, that foot placement is awkward, and that the ability to recover quickly from a misstep is impaired. The resulting disorder is characterized by varying degrees of difficulty in standing and walking; in advanced cases, there is a complete failure of locomotion, although muscular power is retained. The principal features of sensory-ataxic gait are the brusqueness of movement of the legs and stamping of the feet as the foot is forcibly brought down onto the floor (apparently to detect the location of the foot as a substitute for proprioception). The feet are placed far apart to correct the instability, and patients carefully watch both the ground and their legs. As they step out, their legs are flung abruptly forward and outward, in irregular steps of variable length and height. The body is held in a slightly flexed position, and some of the weight is supported on the cane that the severely ataxic patient usually carries. Such patients, when asked to stand with feet together and eyes closed, show greatly increased swaying and usually, the fully expressed Romberg sign with falling off to one side. It is said that in cases of sensory ataxia, the shoes do not show wear in any one place because the entire sole strikes the ground at once. Examination usually discloses a loss of position sense in the feet and legs and usually of vibra tory sense as well. The peripheral or central location of the sensory lesions can be further determined by the state of the tendon reflexes. Formerly, a disordered gait of this type was observed most frequently with tabes dorsalis, hence the term tabetic gait; but it is also seen in Friedreich ataxia and related forms of spinocerebellar degeneration, subacute combined degen eration of the spinal cord (vitamin B12 deficiency), a large number of sensory polyneuropathies, and those cases of multiple sclerosis or compression of the spinal cord (spon dylosis and meningioma the posterior columns 5. If the cerebellar lesions are bilateral, there is often titubation (tremor) of the head and Cerebellar gait is seen most commonly in patients with multiple sclerosis, cerebellar tumors (particularly those affecting the vermis-e. Walking without the support of a cane or the arm of a companion brings out a certain stiffness of the legs and firmness of the muscles. The latter abnormality may be analogous to positive supporting reactions observed in cats and dogs following ablation of the anterior vermis; such animals react to pressure on the foot pad with an extensor thrust of the leg. The drunken patient totters, reels, tips forward and then backward, appear ing each moment to be on the verge of losing his bal ance and falling. Such patients appear indifferent to the quality of their performance, but under certain circumstances they can momentarily correct the defect. As indicated above, the adjectives drunken and reeling are used frequently to describe the gait of cerebellar disease, but the similarities between them are only superficial. The severely intoxi cated patient reels or sways in many different directions and seemingly makes little or no effort to correct the staggering by watching his legs or the ground, as occurs in cerebellar or sensory ataxia. Despite wide excursions of the body and deviation from the line of march, the drunken patient may, for short distances, be able to walk on a narrow base and maintain his balance. In contrast, the patient with cerebellar gait has great difficulty in cor recting his balance if he sways or lurches too far to one side. Milder degrees of the drunken gait more closely resemble the gait disorder that follows loss of labyrin thine function (see earlier discussion). In its purest form it is the result of peroneal nerve or fifth lumbar root damage. Walking is accom plished by excessive flexion at the hip, the leg being lifted abnormally high in order for the foot to clear the ground. Thus there is a superficial similarity to the tabetic gait, especially in cases of severe polyneuropathy, where the features of steppage and sensory ataxia may be com bined. However, patients with steppage gait alone are not troubled by a perception of imbalance; they fall from tripping on carpet edges and curbstones. Foot drop may be unilateral or bilateral and occurs in diseases that affect the peripheral nerves of the legs or motor neurons in the spinal cord, such as chronic acquired neuropathies (diabetic, inflammatory, toxic, and nutritional), Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (peroneal mus cular atrophy), progressive spinal muscular atrophy, and poliomyelitis. It may also be observed in certain types of muscular dystrophy in which the distal musculature of the limbs is involved. A particular disorder of gait, also of peripheral origin and resembling steppage gait, may be observed in patients with painful dysesthesias of the soles of the feet. Because of the exquisite pain evoked by tactile stimulation of the feet, the patient treads gingerly, as though walking bare foot on hot sand or pavement, with the feet rotated in such a way as to limit contact with their most painful portions. The usual cause is one of the painful peripheral neuropa thies (most often alcoholic-nutritional but also toxic and amyloid types), causalgia, or erythromelalgia. This disorder of gait is also seen in a variety of chronic spinal cord diseases involving the dorsolateral and ventral tracts, most often multiple sclerosis, but also including syringomyelia, any type of chronic meningomyelitis, subacute combined system disease of both the pernicious anemia and nonpernicious anemia types, spinal cord compression or traumatic injury, adrenomyeloneuropathy, and familial forms of effects of posterior col umn disease are added, giving rise to a mixed gait disturbance-a spinal spastic ataxia, characteristic of multiple sclerosis and certain spinal cord degenerations such as Friedreich ataxia. Frequently in these diseases, the Parki nsonian and Festinati ng Gait Diminished or absent arm swing, forward bent torso, short or shuffling steps, turning en bloc, hesitation in starting to walk, shuffling, or "freezing" when encounter ing doorways or other obstacles are the features of the parkinsonian gait. When they are joined to the typical tremor, unblinking and mask-like facial expression, gen eral attitude of flexion, and poverty of movement, there can be little doubt as to the diagnosis. The steps are short, and the feet barely clear the ground as the patient shuffles along. Once walking has started, the upper part of the body advances ahead of the lower part, and the patient is impelled to take increasingly short and rapid steps as though trying to catch up to his center of gravity. The steps become more and more rapid, and the patient could easily break into a trot and collide with an obstacle or fall if not assisted. The term festination derives from the Latin Hemiplegic and Paraplegic (Spastic) Gaits the patient with hemiplegia or hemiparesis holds the affected leg stiffly and does not flex it freely at the hip, knee, and ankle. The leg tends to rotate outward to describe a semicircle, first away from and then toward the trunk (circumduction). The foot scrapes the floor, contact being made by the toe and outer sole of the foot. One can recognize a spastic gait by the sound of slow, rhythmic scuffing of the foot and wearing of the medial toe of the shoe. The arm on the affected side is weak and stiff to a variable degree; it is carried in a flexed position and does not swing naturally. This type of gait disorder is most often a sequela of stroke or trauma but may result from any condition that damages the cor ticospinal pathway on one side. The spastic paraplegic or paraparetic gait is, in effect, a bilateral hemiplegic gait. Each leg is advanced slowly and stiffly, with restricted motion at the hips and knees. The legs are extended or slightly bent at the knees and the thighs may be strongly adducted, causing the legs almost to cross as the patient walks (scissor-like gait). The steps are regular and short and the patient advances only with great effort as though wading waist-deep in water. The defect is in stiffness of the stepping mechanism and in propulsion, not in support or equilibrium. A spastic paraparetic gait is the major manifestation of cerebral diplegia (Little disease, a type of cerebral festinare, "to hasten," and appropriately describes the involuntary acceleration or hastening that characterizes the gait of patients with Parkinson disease. Festination may be apparent when the patient is walking forward or ing the legs quickly enough to overtake the center of gravity. The defects are in rocking the body from side to side, so that the feet can clear the floor, and in mov postural support reflexes, demonstrable in the standing patient by falling in response to a push against the ster num or a tug backward on the shoulder.

A tendency to veer to one side gastritis high fiber diet purchase discount prilosec line, as occurs with unilateral cerebellar or vestibular disease gastritis symptoms pain in back buy genuine prilosec on-line, can be brought out by having the patient walk around a chair gastritis images cheap prilosec 10mg with visa. When the affected side is toward the chair, the p atient tends to w alk into it; when it is away from the chair, there is a veering outward in ever-widening circles. More delicate tests of gait are walking a straight line heel to toe ("tandem walking test"), walking back ward, and having the patient arise quickly from a chair, walk briskly, stop and turn suddenly, walk back, and sit down again. Turning the patient three full revolutions with eyes open, first right and then left, each time fol lowed by asking the patient to walk naturally, allows the examiner to stress the vestibular apparatus and to compare the two sides. The patient affected by a ves tibular or cerebellar process will veer to the side of a lesion. Marching in place with eyes closed (Unterberger, or Fukada stepping tests) also reveals a rotation in the yaw plane (rotation around the vertical axis), indicating an asymmetrical disorder in the plane of the horizontal semicircular ducts or their connections. A normal person readily retains his stability or adjusts to modest displace ment of the trunk with a single step, but the parkinsonian patient may lean backward with the upper torso and then stagger or fall unless someone stands by to prevent it. Quite often, one encounters an elderly patient with only the instability and freezing components of the parkinsonian gait disorder, so-called lower-half parkin sonism. Usually, this is not a manifestation of idiopathic Parkinson disease although a few patients are responsive to L-dopa for a brief period. The basis is then probably a particular isolated frontal lobe degeneration (see further on). Within a few years, as pointed out by Factor and colleagues in their two papers, the patient is usually reduced to a chair-bound state. Other very unusual gaits are sometimes observed in Parkinson disease and were particularly prominent in the postencephalitic form, which is now practically extinct. For example, such a patient may be unable to take a step forward or does so only after he takes a few hops or one or two steps backward (aptly mimicked by the Monty Python troupe in their skit, "Ministry of Silly Walks"). Or walking may be initiated by a series of short steps or a series of steps of increasing size. In the more advanced stages, walking becomes impossible owing to torsion of the trunk or the continuous flexion of the legs. Stiff-person syndrome, an unusual nondystonic dis order causing severe axial muscle spasm, imparts a char acteristic appearance of stiffness of the legs and buttock muscles, slow propulsion, and lumbar lordosis; there is sometimes a mild superimposed ataxic disturbance of gait (see Chap. Another unusual disorder affecting the body position during walking is camptocormia, a severe forward bending of the trunk at the waist that is symptomatic of either a dystonia, Parkinson disease, or one of several muscle diseases that focally weaken the extensors of the spine. Kyphosis because of spinal defor mities does the same and all of these conditions cause the patient to walk while looking at the ground beneath the feet, but they rarely cause falling. Chapter 4 more fully describes the general features of the gaits of choreoathetosis and dystonia. Often, walking so preoccupies the patient that talking simultaneously is impossible for him and he must stop to answer a question. Choreoathetotic and Dystonic Gaits Diseases characterized by involuntary movements and dystonic postures seriously affect gait. In fact, a distur bance of gait may be the initial and dominant manifesta tion of such diseases, and the testing of gait often brings out abnormalities of movement of the limbs and posture that are otherwise not conspicuous. As the patient with congenital athetosis or Huntington chorea stands or walks, there is a continuous play of irregular movements affecting the face, neck, hands, and, in the advanced stages, the large proximal joints and Waddling (G l utea l, o r Trendelen burg) Gait this gait is characteristic of the gluteal muscle weakness that is seen in the progressive muscular dystrophies, but it occurs as well in chronic forms of spinal muscular atro phy, in certain inflammatory myopathies, lumbosacral nerve root compression, and with congenital dislocation of the hips. In normal walking, as weight is placed alternately on each leg, the hip is fixated by the gluteal muscles, particu larly the gluteus medius, allowing for a slight rise of the opposite hip and tilt of the trunk to the weight-bearing side. With weakness of the glutei, however, there is a fail ure to stabilize the weight-bearing hip, causing it to bulge outward and the opposite side of the pelvis to drop, with inclination of the trunk to that side. With unilateral gluteal weakness, often the result of damage to the first sacral nerve root, tilting and dropping of the pelvis ("pelvic ptosis") is apparent on only one side as the patient overlifts the leg when walking. In several of the muscular dystrophies, an accen tuation of lumbar lordosis is often seen. Also, childhood cases may be complicated by muscular contractures, leading to an equinovarus position of the foot, so that the waddle is combined with walking on the toes ("toe walking"). There are jerks of the head, grimacing, squirming and twisting movements of the trunk and limbs, and peculiar respiratory noises. One arm may be thrust aloft and the other held behind the body, with wrist and fingers undergoing alternate non-rhythmic flexion and extension, supination and pronation. The head may incline in one direction or the other, the lips alternately retract and purse, and the tongue intermit tently protrudes from the mouth. The legs advance slowly and awkwardly, the result of superimposed invol untary movements and postures. Sometimes the foot is plantarflexed at the ankle and the weight is carried on the toes; or the foot may be dorsiflexed or inverted. An invol untary movement may cause the leg to be suspended in the air momentarily, imparting a lilting or waltzing char acter to the gait, or it may twist the trunk so violently that the patient may fall. In dystonia musculorum deformans and focal dysto nias, the first symptom may be a limp caused by inver sion or plantarflexion of the foot or a distortion of the pelvis as discussed in Chap. One leg may be rigidly extended or one shoulder elevated, and the trunk may assume a position of exaggerated flexion, lordosis, or scoliosis. Because of the muscle spasms that deform the body in this manner, the patient may have to walk with knees flexed. The gait may seem normal as the first steps are taken, the abnormal postures asserting themselves. Toppling Gait Toppling, meaning tottering and falling, occurs with brainstem and cerebellar lesions, especially in the older person following a stroke. It is a frequent feature of the lateral medullary syndrome, in which falling occurs to the side of the infarction. In patients with vestibular neu ronitis, falling also occurs to the same side as the lesion. Walking is percep tibly slower than normal, the body is held stiffly, arm swing is diminished, and there is a tendency to fall back ward-features that are reminiscent of Parkinson disease, although the lack of arm with paralysis of vertical gaze and pseudobulbar fea tures, unexplained falling is often an early and prominent feature. The falls of progressive supranuclear palsy may derive from such a disorder of the righting mechanism. In the advanced stages of Parkinson disease, falling of a similar type may be a serious problem, but it is more surprising how relatively infrequently it occurs. In addi tion, the gait is uncertain and hesitant-features that are enhanced, no doubt, by the hazard of falling unpredict ably. The cause of the toppling phenomenon is unclear; it does not have its basis in weakness, ataxia, or loss of deep sensation. It appears to be a disorder of balance that is occasioned by precipitant action or the wrong placement of a foot and by a failure of the righting reflexes. In a related defect caused by a vestibular disorder, the patient may describe a sense of being pushed (pul sion) rather than of imbalance. In midbrain disease, including progressive supranuclear palsy, a remarkable feature is the lack of appreciation of a sense of imbalance. Sudarsky and Simon quantified these defects by means of high-speed cameras and com puter analysis. They reported a reduction in height of step, an increase in sway, and a decrease in rotation of the pelvis and counter-rotation of the torso. In reaction to a percep tion of severe imbalance, which is characteristic of the disorder, the patient assumes a widened and often stiff legged stance. Frontal Lobe Disorders of Gait Standing and walking may be severely disturbed by diseases that affect the frontal lobes, particularly their medial parts and their connections with the basal ganglia. This disorder is sometimes spoken of as a frontal lobe as an "apraxia of gait" among numerous other labels, because the difficulty in walking cannot be accounted for by weakness, loss of sensation, cerebellar incoordina tion, or basal ganglionic abnormality. Whether the gait disorder should be designated as an apraxia, in the sense of the original concept of the loss of ability to perform a learned act, is questionable, as walking is instinctual and not learned. Patients with so-called apraxia of gait do not have apraxia of individual limbs, particularly of the lower limbs; conversely, patients with apraxia of the limbs usually walk normally. More likely, the frontal gait disorder represents a loss of integration, at the cortical and basal ganglionic levels, of the essential elements of stance and locomotion that are acquired in infancy and often lost in old age. Patients typically assume a posture of slight flexion with the feet placed farther apart than normal. At times they halt, unable to advance without great effort, although they do much better with a little assistance or with exhortation to walk in step with the examiner or to a marching cadence. Walking and turning are accom plished by a series of tiny, uncertain steps that are made with one foot, the other foot being planted on the floor as a pivot. Certainly it cannot be categorized as an ataxic or spastic gait or what has been described as an "apraxic" gait; nor does it have more than a superficial resemblance to the parkinsonian gait. Its main features slowed cadence, widened base and short steps-are the natural compensations observed in patients with all man ner of gait disorders. Patients with the gait disorder of function, they are better able to carry out the motions of ziness, but most have difficulty in articulating the exact problem. Like most patients with disorders of frontal lobe stepping while supine or sitting but have difficulty in taking steps when upright or attempting to walk. If these ing table and in and out of bed, they display poor man agement of the entire axial musculature, moving their bodies without shifting the center of gravity or adjusting their limbs appropriately. The erect posture is assumed in an awkward manner-with hips and knees only slightly flexed and stiff and a delay in swinging the legs over the side of the bed. The initiation of walk ing becomes progressively more difficult; in advanced cases, the patient makes only feeble, abortive stepping movements in place, unable to move his feet and legs forward; eventually, the patient can make no stepping movements whatsoever, as though his feet were glued to the floor. These late phenomena have been referred to as "magnetic feet" and the difficulty initiating gait as "slip ping clutch" syndrome (Denny-Brown) or "gait ignition failure" (Atchison et al). In some patients, difficulty in the initiation of gait may be an early and apparently isolated phenomenon but invariably, with the passage of time, the other features of the frontal lobe gait disorder become evident. Until the late stages of the process, these patients, while seated or supine are able to make complex move ments with their legs, such as drawing imaginary figures or pedaling a bicycle and, quite remarkably, to simulate the motions of walking, all at a time when their gait is seriously impaired. Eventually, however, all movements of the legs become slow and awkward, and the limbs, when passively moved, offer variable counterresistance (paratonia or gegenhalten).

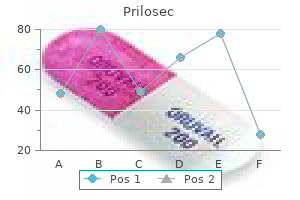

The latter are accomplished via efferent projections from the dentate nucleus to the ventrolateral thalamus and motor cortex lymphocytic gastritis symptoms treatment purchase prilosec 20 mg without a prescription. The dentatal neurons were shown to fire just before the onset of volitional movements gastritis gurgling stomach order prilosec 10 mg mastercard, and inac tivation of the dentatal neurons delayed the initiation of such movements gastritis symptoms temperature buy prilosec 40 mg overnight delivery. The interpositus nucleus also receives cerebrocortical projections via the pontocerebellar sys tem; in addition, it receives spinocerebellar projections via the intermediate zone of the cerebellar cortex. The latter projections convey information from Golgi tendon organs, muscle spindles, cutaneous afferents, and spinal cord interneurons involved in movement. Also, the prepositus nucleus appears to be responsible for making volitional oscillations (alternating movements). Its cells fire in tandem with these actions, and their regularity and amplitude are impaired when these cells are inactivated. These investigators studied the effects of cooling the deep nuclei during a projected movement in the macaque monkey. Their observations, coupled with established anatomic data, permit the following conclusions. The fastigial nucleus controls antigravity and other muscle synergies in standing and walking; ablation of this nucleus greatly impairs these motor activities. Neuronal Organ ization of the Cerebel lar Cortex Coordinated and fluid movements of the limbs and trunk result from a neuronal organization in the cerebellum that permits an ongoing and almost instantaneous com parison between desired and actual movements while the movements are being carried out. Also, it has been estimated that there are 40 times more afferent axons than efferent axons in the various cerebellar pathways-a reflection of the enormous amount of incoming (sensory) information that is required for the control of motor function. The cerebellar cortex is configured as a stereotyped three-layered structure containing five types of neurons. In its relatively regular geometry, it is similar to the columnar architecture of the cerebral cortex, but it differs in the greater degree of intracortical feedback between neurons and the convergent nature of input fibers. The outermost "molecular" layer of the cerebellum contains two types of inhibitory neurons, the stellate cells and the basket cells. They are interspersed among the dendrites of the Purkinje cells, the cell bodies of which lie in the underlying layer. The Purkinje cell axons constitute the main output of the cerebellum, which is directed at the deep cerebellar and vestibular nuclei described above. The innermost "granular" layer contains an enormous number of densely packed granule cells and a few larger Golgi interneurons. Axons of the granule cells travel long distances as "parallel fibers," which are oriented along the long axis of the folia and form excitatory synapses with Purkinje cells. Each Purkinje cell is influenced by as many as a million granule cells to produce a single electrical "simple spike. They enter through all three cerebel lar peduncles, mainly the middle (pontine input) and inferior (vestibulocerebellar) ones. Mossy fibers ramify in the granule layer and excite Golgi and granule neurons through special synapses termed cerebellar glomeruli. The other main afferent input is via the climbing fibers, which originate in the inferior olivary nuclei (olives) and communicate somatosensory, visual, and cerebral cortical signals. The climbing fibers, so named because of their vine-like configuration around Purkinje cells and their axons, preserve a topographic arrange ment from olivary neuronal groups; a similar topo graphic arrangement is maintained in the Purkinje cell projections. The climbing fibers have specific excitatory effects on Purkinje cells that result in prolonged "complex spike" depolarizations. The firing of stellate and basket cells is facilitated by the same parallel fibers that excite Purkinje cells, and these smaller cells, in turn, inhibit the Purkinje cells. These reciprocal relationships form the feedback loops that permit the exquisitely delicate inhibi tory smoothing of limb movements that are lost when the organ is damaged. The uniform cortical structure of the cerebellum can reasonably lead to the conjecture that the organ has similar effects on all parts of the cerebrum to which it has projections (cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus, etc. It would follow that the activities of these cerebral struc tures (motor, cognitive, sensory) may be modulated in similar ways by cerebellar activity. Neurochem ical Considerations A number of biochemical considerations are of inter est. Four of the five cell types of the cerebellar cortex (Purkinje, stellate, basket, Golgi) are inhibitory; the granule cells are an exception and are excitatory. Afferent fibers to the cerebellum are of three types, two of which have been mentioned above: (1) Mossy fibers, which are the main afferent input to the cerebellum, utilize aspartate. They are of two types: dopaminergic fibers, which arise in the ventral mesencephalic tegmentum and project to the interpositus and dentate nuclei and to the granule and Purkinje cells throughout the cortex, and serotonergic neurons, which are located in the raphe nuclei of the brain stem and project diffusely to the granule cell and molecu lar layer. For Babinski, the essential function of the cerebellum was the orchestration of mus cle synergies in the performance of voluntary movement. This deficit, most apparent in the execution of rap idly alternating movements, was referred to by Babinski as dys- or adiadochokinesis, as discussed below in the description of ataxia. Anatomic organization of the cerebellar cortex in a longitudinal and transverse section of a folium. Shown are the relationships between (a) climbing fibers and Purkinje cells, (b) mossy fibers and both granule cells and Golgi cells, and (c) the parallel fibers that course longitudinally and connect these three main cell types. Holmes s ummarized the effects of cerebellar disease as being in the acceleration and deceleration of movement. He characterized the effects in a more fundamental way than had Babinski, descn bing them as defects in the tremor, and the inability to check the displacement of an outstretched limb, both of which he elegantly described, he attributed to this latter defect (see further on). Gilman and colleagues have provided evidence that more than hypoto nia is involved in the tremor of cerebellar incoordination. They found that deafferentation of the forelimb of a mon key resulted in dysmetria and kinetic tremor; subsequent cerebellar ablation significantly increased both the dysmet ria and tremor, indicating the presence of a mechanism as yet unidentified in addition to depression of the fusimotor efferent-spindle afferent circuit. Parts of the hypotheses of both Babinski and Holmes have been sustained by modern physiologic and clinical rate, range, and force of movement, resulting in an undershooting or overshooting of the target. He used the term decomposition to describe the fragmentation of a smooth movement into a series of irregular, jerky components. Most of the lesions that occur in humans do not respect the boundaries established by experimen tal anatomists. Clinical observations affirm what was stated above that lesions of the cerebellum in humans give rise to the following abnormalities: (1) incoordination (ataxia) of volitional movement; Mossy -1 fiber Golgi -u cell Inhibitory cortical side loop (2) a characteristic tremor ("inten tion", or ataxic tremor, by which is meant a side-to-side oscillation as movement approaches a target), described in detail in Chap. Dysarthria, a common feature of cerebellar dis neurons Precerebellar nucleus cell (spinocerebellar pathways, brainstem reticular nuclei, pontine nuclei, etc. In addition, the stability of conjugate eye movements is affected, giving rise to nystagmus. Extensive lesions of one cerebellar hemisphere, especially of the anterior lobe, cause mild hypotonia, postural abnormalities, ataxia, and a mild weakness of the ipsilateral arm and leg perceived by the patient. Lesions of the deep nuclei and cerebellar peduncles have the same effects as extensive hemispheral lesions. If the lesion involves a limited portion of the cerebellar cortex and subcortical white matter, there may be sur prisingly little disturbance of function, or the abnormal ity may be greatly attenuated with the passage of time. For example, a congenital developmental defect or an early life sclerotic cortical atrophy of half of the cerebel lum may produce no clinical abnormalities. Lesions involving the superior cerebellar peduncle or the den tate nucleus cause the most severe and enduring cere bellar symptoms, which manifest mostly as ataxia in the ipsilateral limbs. Disorders of stance and gait depend more on vermian than on hemispheral or peduncular involvement. Damage in the inferior cerebellum causes vestibulocerebellar symptoms-namely, dizziness, ver tigo, vomiting, and nystagmus-in varying proportions. These symptoms often share with disturbances of the vestibular system the feature of worsening with changes in head position. The main output of the deep cerebellar nuclei is excitatory and is transmit ted through mossy and climbing fibers. This "main loop" is modu lated by an inhibitory cortical loop, which is effected by Purkinje cell output but indirectly includes the other main cell types through their connections with Purkinje cells. In an analysis of rapid (ballistic) movements, Hallett and colleagues have demonstrated that with cerebel lar lesions, there is a prolongation of the interval between the commanded act and the onset of movement. More prominently, there is a derangement of the normal ballis tic triphasic agonist-antagonist-agonist motor sequence, referred to in Chaps. The agonist burst may be too long or too short, or it may continue into the antagonist burst, resulting in excessive agonist-antagonist cocontrac tion at the onset of movement. These findings may explain what was described by Babinski and Holmes as asynergia, decomposition of movement, and certainly explain dys metria. Diener and Dichgans confirmed these fundamental abnormalities in the timing and amplitude of reciprocal inhibition and of cocontraction of agonist-antagonist mus cles and remarked that these were particularly evident in pluriarticular movements. Following Babinski, the terms dyssynergia, dysmetria, and dysdiadochoki nesis came into common usage to describe cerebellar abnormalities of movement. In performing these tests, the patient should be asked to move the limb to the target accurately and rapidly. In a detailed electrophysi ologic analysis of this defect mentioned earlier, Hallett and colleagues noted, in both slow and fast movements, that the initial agonist burst was prolonged and the peak force of the agonist contraction was reduced. Also, there is irregularity and slowing of the movement itself, in both acceleration and deceleration. These abnormalities are particularly prominent as the finger or toe approaches its target. All of the foregoing defects in volitional move ment are evident in acts that require alternation or rapid change in direction of movement, such as prona tion-supination of the forearm or successive touching of each fingertip to the thumb. The normal rhythm of these movements is interrupted by irregularities of force and speed. Even a simple movement may be fragmented ("decomposition" of movement), each component being effected with greater or lesser force than is required.

Cheap prilosec 20 mg without a prescription. Reflux Esophagitis 1.

References

- Scheiman JM. NSAIDs, gastrointestinal injury, and cytoprotection. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996; 25:279-98.

- OiFlynn KJ, Murphy R, Thomas DG: Neurogenic bladder dysfunction in lumbar intervertebral disc prolapse, Br J Urol 69(1):38n40, 1992.

- Philip J, Manikandan R, et al: Ejaculatory-duct calculus causing secondary obstruction and infertility, Fertil Steril 88(3):706 e709n706 e711, 2007.

- Aouba A, Diop S, Saadoun D, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension as initial manifestation of intravascular lymphoma: a case report. Am J Hematol 2005;79:46-9.

- Nyhan W, Bay C, Webb E, et al. Neurologic nonmetabolic presentation of propionic acidemia. Arch Neurol 1999;56:1143.

- Levinson A, Hopewell PC, Stites DP, et al. Coexistent lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, pernicious anemia, and agammaglobulinemia: comment on autoimmune pathogenesis. Arch Intern Med 1976;136:213-6.