Marko Bukur, MD

- Fellow in Trauma and Surgical Critical Care,

- University of Southern California? Keck School of

- Medicine, CA, USA

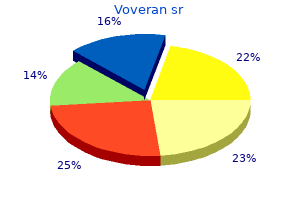

In docu mented coronary spasm muscle relaxant yellow pill with m on it order cheap voveran sr, calcium channel blockers and nitrates may be effective spasms on left side of abdomen best purchase voveran sr. Usual therapy for heart failure or conduction system disease is warranted when symptoms occur muscle relaxant liquid form buy cheapest voveran sr and voveran sr. Other illicit drug use has been associated with myo carditis in various case reports. The problem of cardiovascular side effects from cancer chemotherapy agents is a growing one. Heart failure can be expected in 5% of patients treated with a cumulative dose of 400-450 mg/m2, and this rate is doubled if the patient is over age 65. The maj or mechanism of cardiotoxicity is thought to be due to oxidative stress inducing both apoptosis and necrosis of myocytes. This is the rationale behind the superoxide dismutase mimetic and iron-chelat ing agent, dexrazoxane, to protect from the injury. In patients receiving chemotherapy, it is important to look for subtle signs of cardiovascular compromise. Multiple biomarkers may appear early in the course of myocardial injury (especially troponin and myeloperoxidase) and may allow for early detection of cardiotoxicity before other signs become evident. There is some evidence that beta blocker therapy may reduce the negative effects on myo cardial function. This is a large group of heteroge neous myocardial disorders characterized by reduced myocardial contractility in the absence of abnormal load ing conditions such as with hypertension or valvular dis ease. The prevalence averages 36 cases/ 1 00,000 in the United States and accounts for approximately 1 0,000 deaths annually. Endocrine and metabolic causes include obesity, diabetes, thyroid disease, acromegaly, and growth hormone deficiency. Dilated cardio myopathy may also be caused by prolonged tachycardia and right ventricular pacing. Peripartum cardiomyopathy and stress-induced disease (tako-tsubo) are discussed separately. Once heart failure becomes evident or significant con duction system disease becomes manifest, the patient should be evaluated and monitored by a cardiologist in case myocardial dysfunction worsens and further interven tion becomes warranted. Cardiovascular side effects of cancer thera pies: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Early increases in multiple biomarkers predict subse quent cardiotoxicity in patients with breast cancer treated with doxorubicin, taxanes, and trastuzumab. Beta-adrenergic blockade for anthracycline- and trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity: is prevention better than cure Symptoms and Signs In most patients, symptoms of heart failure develop gradu ally. It is important to seek out a history of familial dilated cardiomyopathy and to identify behaviors that might pre dispose patients to the disease. In severe heart failure, Cheyne-Stokes breathing, pulsus alternans, pallor, and cyanosis may be present. Other common abnormalities include left bundle branch block and ventricular or atrial arrhyth mias. The chest radiograph reveals cardiomegaly, evidence for left and/or right heart failure, and pleural effusions (right more than left). Other biomarkers, such as troponin I or T and measures that reflect inflammation, oxidative stress, neurohormonal disarray and myocardial or matrix remod eling are under investigation for their ability to guide therapy. Mitral Doppler inflow patterns also help in the diagnosis of concomitant diastolic dysfunction. Exercise or pharmacologic stress myocardial perfusion imaging may uncover underlying coronary disease. Myocardial biopsy is rarely useful in establishing the diagnosis, although occasionally the underlying cause (eg, sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis) can be discerned. Treatment the management of heart failure is outlined in the section on heart failure. A few beta-blockers, including bisoprolol, carvedilol, and sus tained-release metoprolol, have been shown to reduce mortality and should be preferentially used if possible. Calcium channel blockers should be avoided except as necessary to control ventricular response in atrial fibrilla tion or flutter. If congestive symptoms are present, diuretics and an aldosterone antagonist should be added. Care in the use of aldo sterone antagonists is warranted when the glomerular fil tration rate is less than 30 mL/min/ 1. Given the question of abnormal nitric oxide utilization in blacks, the use of hydralazine-nitrate combination therapy is recommended in this population. When atrial fibrillation is present, heart rate control is vital if sinus rhythm cannot be established or maintained. There are little data, however, to suggest an advantage of sinus rhythm over atrial fibrillation on long-term out comes. Cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training have consistently been found to improve clinical status. Few cases of cardiomyopathy are amenable to specific therapy for the underlying cause. Alcohol use should be discontinued, since there is often marked recovery of car diac function following a period of abstinence in alcoholic cardiomyopathy. Endocrine causes (hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, acromegaly, and pheochromocytoma) should be treated. Arterial and pulmonary emboli are more common in dilated car diomyopathy than in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Suitable candidates may benefit from long-term anticoagulation, and all patients with atrial fibrillation should be so treated. The newer targeted antithrombotic agents are appropriate unless there is associated mitral stenosis. When to Refer Patients with new or worsened symptoms of heart failure with dilated cardiomyopathy should be referred to a cardi ologist. When to Adm it Patients with hypoxia, fluid overload, or pulmonary edema not readily resolved in an outpatient setting should be admitted. Presents as an acute anterior myocardial i nfa rc tion, but corona ries normal at card ia c catheterization. I maging reveals apical left ventricular bal looning due to a nteroapical stu nning of the myocardium. Prognosis the prognosis of dilated cardiomyopathy without clinical heart failure is variable, with some patients remaining sta ble, some deteriorating gradually, and others declining rapidly. Once heart failure is manifest, the natural history is similar to that of other causes of heart failure, with an annual mortality rate of around 1 1 - 1 3%. In a 2000 review of survival in dilated cardiomyopathy, the underlying cause of heart failure has prognostic value in patients with unex plained cardiomyopathy. Patients with peripartum cardio myopathy or stress-induced cardiomyopathy appear to have a better prognosis than those with other forms of cardiomyopathy. Overall, prognosis is good unless there is a serious complication (such as mitral regurgitation, ventricular rupture, or ven tricular tachycardia). Virtually any event that triggers excess catecholamines has been implicated in a wide number of case reports. First described in 1 990, it pre dominantly affects women (up to 90%), primarily postmeno pausal. The interventricular septum may be disproportionately involved (asymmetric septal hypertrophy), but in some cases the hypertrophy is localized to the mid-ventricle or to the apex. The amount of obstruction is preload and afterload dependent and can vary from day to day. Prognosis In a 2015 registry of 1759 patients, the rate of severe in hospital complications, including shock and death were similar between those with an acute coronary syndrome and tako-tsubo. Men appear to be at higher risk for major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events during the first 30 days following the event. During long-term follow-up the rate of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events was 9. A mid ventricular obstructive form is also known where there is contact between the septum and papillary muscles. A hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the elderly (usually in association with hypertension) has also been defined as a distinct entity (often a sigmoid interventricular septum is noted). Mitral regurgitation is variable and often dynamic, depending on the degree of outflow tract obstruction. Symptoms and Signs the most frequent symptoms are dyspnea and chest pain (see Table 1 0 - 1 8). Ven tricular arrhythmias are also common, and sudden death may occur, often after extraordinary exertion. Myo cardial perfusion imaging may suggest septal ischemia in the presence of normal coronary arteries. Frequently, coronary arterial bridging (squeezing of the coronary in systole) occurs, especially in the septal arteries. Treatment B eta-blockers should be the initial medication in symp tomatic individuals, especially when dynamic outflow obstruction is noted on the echo cardiogram. Calcium channel blockers, especially vera pamil, have also been effective in symptomatic patients. Their effect is due primarily to improved diastolic func tion; however, their vasodilating actions can also increase outflow obstruction and cause hypotension. Disopyramide is also effective because of its negative inotropic effects; it is usually used as an addition to the medical regimen rather than as primary therapy or to help control atrial arrhyth mias. Patients do best in sinus rhythm, and atrial fibrillation should be aggressively treated with antiarrhythmics or radiofre quency ablation.

Two pneumococcal vaccines for adults are available and approved for use in the United States: one containing capsular polysaccharide antigens of 23 common strains of S pneumoniae in use for many years (Pneumovax 23) and a conjugate vaccine containing 13 common strains approved for adult use in 20 1 1 (Prevnar- 13) muscle relaxant alcoholism order voveran sr 100mg visa. Current recom mendations are for sequential administration of the two vaccines in those age 65 years or older and in immunocom promised persons spasms knee voveran sr 100 mg low cost. Immunocompromised patients and those at highest risk for fatal pneumococcal infections should receive a single revaccination of the 23-valent vaccine 6 years after the first vaccination regardless of age muscle relaxant tincture buy cheap voveran sr 100mg. Immuno competent persons 65 years of age or older should receive a second dose of the 23-valent vaccine if the patient first received the vaccine 6 or more years previously and was under 65 years old at the time of first vaccination. The seasonal influenza vaccine is effective in preventing severe disease due to influenza virus with a resulting posi tive impact on both primary influenza pneumonia and secondary bacterial pneumonias. The seasonal influenza vaccine is administered annually to persons at risk for complications of influenza infection (age 65 years or older, residents of long-term care facilities, patients with pulmo nary or cardiovascular disorders, patients recently hospi talized with chronic metabolic disorders) as well as health care workers and others who are able to transmit influenza to high-risk patients. Hospitalized patients who would benefit from pneumo coccal and influenza vaccines should be vaccinated during hospitalization. The vaccines can be given simultaneously, and may be administered as soon as the patient has stabilized. First-line therapy in hospitalized patients is a respiratory fluoroquinolone (eg, moxifloxacin, gemi floxacin, or levofloxacin) or the combination of a macrolide (clarithromycin or azithromycin) plus a beta-lactam (cefo taxime, ceftriaxone, or ampicillin) (see Table 9-9). However, no studies in hospitalized patients demonstrated superior outcomes with intravenous antibiotics compared with oral antibiotics, as long as patients were able to tolerate the oral therapy and. Emergency management of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia: what is new since the 2007 Infectious Diseases Society of America/ American Thoracic Society guidelines. Pneumonia: diagnosis and management of community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults. Corticosteroid therapy for patients hospi talized with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Unit Admission Decision Expert opinion has defined major and minor criteria to identify patients at high risk for death. Major criteria are septic shock with need for vasopressor support and respi ratory failure with need for mechanical ventilation. Minor criteria are respiratory rate 30 breaths or more per minute, hypoxemia (defined as Pao / Fro 2 250 or less), hypothermia (core temperature less than 36. In addition to pneumonia-specific issues, good clinical practice always makes an admission decision in light of the whole patient. Especially common in patients requiring i ntensive care or mechanical ventilation. General Considerations Hospitalized patients carry different flora with different resistance patterns than healthy patients in the community, and their health status may place them at higher risk for more severe infection. Other medical or psychosocial needs (such as cognitive dysfunction, psychiatric disease, homelessness, drug abuse, lack of outpatient resources, or poor overall functional status). Some community members have extensive contact with the healthcare system and carry flora that more closely resemble hospitalized patients than healthy community residents. Initial management and antibiotic therapy should be targeted to the common flora and specific risk factors for severe disease. Definitive identification of the infectious cause of a lower respiratory infection is rarely available on presentation, thus, rather than pathogen-directed antibiotic treatment, the choice of empiric therapy is informed by epidemiologic and patient data. Since access to the lower respiratory tract occurs primarily through microaspiration, nosocomial pneumonia starts with a change in upper respiratory tract flora. Colonization of the pharynx and possibly the stomach with bacteria is the most important step in the pathogenesis of nosocomial pneumonia. Pharyngeal colonization is promoted by exog enous factors (eg, instrumentation of the upper airway with nasogastric and endotracheal tubes; contamination by dirty hands, equipment, and contaminated aerosols; and treat ment with broad-spectrum antibiotics that promote the emergence of drug-resistant organisms) and patient factors (eg, malnutrition, advanced age, altered consciousness, swallowing disorders, and underlying pulmonary and sys temic diseases). Within 48 hours of admission, 75% of seri ously ill hospitalized patients have their upper airway colonized with organisms from the hospital environment. Impaired cellular and mechanical defense mechanisms in the lungs of hospitalized patients raise the risk of infec tion after aspiration has occurred. Anaerobic organisms (bacteroides, anaerobic streptococci, fusobacte rium) may also cause pneumonia in the hospitalized patient; when isolated, they are commonly part of a poly microbial flora. Mycobacteria, fungi, chlamydiae, viruses, rickettsiae, and protozoal organisms are uncommon causes of nosocomial pneumonias. Because of the high mortality rate, therapy should be started as soon as pneu monia is suspected. There is no consensus on the best regi mens because this patient population is heterogeneous and local flora and resistance patterns must be taken into account. After results of sputum, blood, and pleural fluid cul tures are available, it may be possible to de-escalate initially broad therapy. Duration of antibiotic therapy should be individualized based on the pathogen, severity of illness, response to therapy, and comorbid conditions. Hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator associated pneumonia: recent advances in epidemiology and management. Healthcare-associated pneumonia does not accurately identify potentially resistant pathogens: a system atic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology, antibiotic therapy and clinical out comes of healthcare-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients: a Spanish cohort study. Laboratory Findings Diagnostic evaluation for suspected nosocomial pneumo nia includes blood cultures from two different sites. Blood cultures can identify the pathogen in up to 20% of all patients with nosocomial pneumonias; positivity is associ ated with increased risk of complications and other sites of infection. The assessment of oxygenation by an arterial blood gas or pulse oximetry determination helps define the severity of illness and determines the need for assisted ventilation. Thoracentesis for pleural fluid analysis should be consid ered in patients with pleural effusions. Gram stains and cultures of sputum are neither sensitive nor specific in the diagnosis of nosoco mial pneumonias. The identification of a bacterial organ ism by culture of sputum does not prove that the organism is a lower respiratory tract pathogen. However, it can be used to help identify bacterial antibiotic sensitivity patterns and as a guide to adjusting empiric therapy. Endotracheal aspiration cultures have significant negative predictive value but limited positive predictive value in the diagnosis of specific infectious. I nfiltrate in dependent lung zone, with single or multiple areas of cavitation or pleura l effusion. Cefepime, 1 -2 g i ntravenously twice a day or ceftazidi me, 1 -2 g intravenously every 8 hours b. Levofloxacin, 750 mg intravenously daily or ciprofloxacin, 400 mg i ntravenously every 8- 1 2 hours b. I ntravenous va ncomycin (i nterval dosing based on renal fu nction to achieve serum trough concentration 1 5-20 mcg/m l) or b. General Considerations Aspiration of small amounts of oropharyngeal secretions occurs during sleep in normal individuals but rarely causes disease. Sequelae of aspiration of larger amounts of mate rial include nocturnal asthma, chemical pneumonitis, mechanical obstruction of airways by particulate matter, bronchiectasis, and pleuropulmonary infection. Individu als predisposed to disease induced by aspiration include those with depressed levels of consciousness due to drug or alcohol use, seizures, general anesthesia, or central nervous system disease; those with impaired deglutition due to esophageal disease or neurologic disorders; and those with tracheal or nasogastric tubes, which disrupt the mechani cal defenses of the airways. Periodontal disease and poor dental hygiene, which increase the number of anaerobic bacteria in aspirated material, are associated with a greater likelihood of anaero bic pleuropulmonary infection. Aspiration of infected oropharyngeal contents initially leads to pneumonia in dependent lung zones, such as the posterior segments of the upper lobes and superior and basilar segments of the lower lobes. Body position at the time of aspiration deter mines which lung zones are dependent. By the time the patient seeks medical attention, necrotizing pneumonia, lung abscess, or empy ema may be apparent. In most cases of aspiration and necrotizing pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema, multiple species of anaerobic bacteria are causing the infection. Most of the remaining cases are caused by infection with both anaerobic and aero bic bacteria. Prevotella melaninagenica, Peptostreptocaccus, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Bacteroides species are commonly isolated anaerobic bacteria. Symptoms and Signs Patients with anaerobic pleuropulmonary infection usu ally present with constitutional symptoms, such as fever, weight loss, and malaise. Cough with expectoration of foul-smelling purulent sputum suggests anaerobic infec tion, though the absence of productive cough does not rule out such an infection. Patients are rarely edentulous; if so, an obstructing bronchial lesion is usually present. Laboratory Findings Expectorated sputum is inappropriate for culture of anaer obic organisms because of contaminating mouth flora. Representative material for culture can be obtained only by transthoracic aspiration, thoracentesis, or bronchoscopy with a protected brush. Transthoracic aspiration is rarely indicated, because drainage occurs via the bronchus and anaerobic pleuropulmonary infections usually respond well to empiric therapy. Although almost any pathogen can cause pneumonia in an immunocompromised host, two clinical tools help the clinician narrow the differential diagnosis. Defects in humoral immunity predispose to bacterial infections; defects in cellular immunity lead to infections with viruses, fungi, mycobacteria, and protozoa. Neutrope nia and impaired granulocyte function predispose to infec tions from S aureus, Aspergillus, gram-negative bacilli, and Candida. Second, the time course of infection also provides clues to the etiology of pneumonia in immunocompro mised patients. A fulminant pneumonia is often caused by bacterial infection, whereas an insidious pneumonia is more apt to be caused by viral, fungal, protozoal, or myco bacterial infection.

Buy voveran sr 100mg on line. skeletal muscle relaxant 3 - spasmolytics - arabic.

Endoscopic evaluation is also warranted when symp toms fail to respond to initial empiric management strate gies within 4-8 weeks or when frequent symptom relapse occurs after discontinuation of antisecretory therapy spasms rectum best buy for voveran sr. Other Conditions Diabetes mellitus muscle relaxant 2mg generic voveran sr 100 mg amex, thyroid disease back spasms yoga discount 100 mg voveran sr, chronic kidney disease, myocardial ischemia, intra-abdominal malignancy, gastric volvulus or paraesophageal hernia, chronic gastric or intes tinal ischemia, and pregnancy are sometimes accompanied by dyspepsia. Symptoms and Signs Given the nonspecific nature of dyspeptic symptoms, the history has limited diagnostic utility. It should clarify the chronicity, location, and quality of the discomfort, and its relationship to meals. The discomfort may be characterized by one or more upper abdominal symptoms including epigastric pain or burning, early satiety, postprandial full ness, bloating, nausea, or vomiting. Concomitant weight loss, persistent vomiting, constant or severe pain, dyspha gia, hematemesis, or melena warrants endoscopy or abdominal imaging. Potentially offending medications and excessive alcohol use should be identified and discontin ued if possible. Recent changes in employment, marital discord, physical and sexual abuse, anxiety, depression, and fear of serious disease may all contribute to the develop ment and reporting of symptoms. Patients with functional dyspepsia often are younger, report a variety of abdominal and extragastrointestinal complaints, show signs of anxiety or depression, or have a history of use of psychotropic medications. The symptom profile alone does not differentiate between functional dyspepsia and organic gastrointestinal disorders. Based on the clinical history alone, primary care clinicians misdiagnose nearly half of patients with peptic ulcers or gastroesophageal reflux and have less than 25% accuracy in diagnosing functional dyspepsia. Signs of seri ous organic disease such as weight loss, organomegaly, abdominal mass, or fecal occult blood are to be further evaluated. Other Tests In patients with refractory symptoms or progressive weight loss, antibodies for celiac disease or stool testing for ova and parasites or Giardia antigen, fat, or elastase may be consid ered. Ambulatory esophageal pH-impedance testing may be of value when atypical gastroesophageal reflux is suspected. Treatment Initial empiric treatment is warranted for patients who are younger than 50 years and who have no alarm features (defined above). All other patients as well as patients whose symptoms fail to respond or relapse after empiric treat ment should undergo upper endoscopy with subsequent treatment directed at the specific disorder (eg, peptic ulcer, gastroesophageal reflux, cancer). Most patients will have no significant findings on endoscopy and will be given a diagnosis of functional dyspepsia. Laboratory Findings In patients older than age of 50 years, initial laboratory work should include a blood count, electrolytes, liver enzymes, calcium, and thyroid function tests. In patients younger than 50 years with uncomplicated dyspepsia (in whom gastric cancer is rare), initial noninvasive strategies should be pursued. In most clinical settings, a noninvasive test for H pylori (urea breath test, fecal antigen test, or IgG serology) should be performed first. Although serologic tests are inexpensive, performance characteristics are poor in low-prevalence populations, whereas breath A. Empiric Therapy Young patients with uncomplicated dyspepsia may be treated empirically with either a proton pump inhibitor or evaluated with a noninvasive test for H pylori, followed if positive by treatment. The prevalence of H pylori in the population influences recommendations for the timing of these empiric therapies. In clinical settings in which the prevalence of H pylori infection in the population is low (less than 1 0%), it may be more cost-effective to initially treat patients with a 4-week trial of a proton pump inhibi tor. Patients who have symptom relapse after discontinua tion of the proton pump inhibitor should be tested for H pylori and treated if results are positive. Herbal therapies (peppermint, cara way) may offer benefit with little risk of adverse effects. Effect of amitriptyline and escitalopram on functional dyspepsia: a multicenter, randomized controlled study. For patients who have symptom relapse after discontinuation of the proton pump inhibitor, inter mittent or long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy may be considered. For patients in whom test results are posi tive for H pylori, antibiotic therapy proves definitive for patients with underlying peptic ulcers and may improve symptoms in a small subset (less than 10%) of infected patients with functional dyspepsia. Patients with persistent dyspepsia after H pylori eradication can be given a trial of proton pump inhibitor therapy. Vomiting often follows, as does retching (spasmodic respi ratory and abdominal movements). Vomiting should be distinguished from regurgitation, the effortless reflux of liquid or food stomach contents; and from rumination, the chewing and swallowing of food that is regurgitated voli tionally after meals. The brainstem vomiting center is composed of a group of neuronal areas (area postrema, nucleus tractus solitarius, and central pattern generator) within the medulla that coordi nate emesis. For example, patients receiving chemotherapy may start vomiting in anticipation of its administration. This region may be stimulated by drugs and chemotherapeutic agents, toxins, hypoxia, uremia, acidosis, and radiation therapy. Although the causes of nausea and vomiting are many, a simplified list is provided in Table 1 5 - 1. General measures-Most patients have mild, intermit tent symptoms that respond to reassurance and lifestyle changes. Patients with postprandial symptoms should be instructed to consume small, low-fat meals. A food diary, in which patients record their food intake, symptoms, and daily events, may reveal dietary or psychosocial precipi tants of pain. Pharmacologic agents-Drugs have demonstrated lim ited efficacy in the treatment of functional dyspepsia. Antisecretory therapy for 4-8 weeks with oral proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, esomeprazole, or rabeprazole 20 mg, dexlan soprazole or lansoprazole 30 mg, or pantoprazole 40 mg) may benefit 1 0 - 1 5 % of patients, particularly those with dyspepsia characterized as epigastric pain ("ulcer-like dys pepsia") or dyspepsia and heartburn ("reflux-like dyspep sia"). Low doses of antidepressants (eg, desipramine or nortriptyline, 25-50 mg orally at bedtime) benefit some patients, possibly by moderating visceral afferent sensitiv ity. Meto clopramide (5- 1 0 mg three times daily) may improve symptoms, but improvement does not correlate with the presence or absence of gastric emptying delay. Anti-H pylori treatment-Meta-analyses have suggested that a small number of patients with functional dyspepsia (less than 1 0%) derive benefit from H pylori eradication therapy. Therefore, patients with functional dyspepsia should be tested and treated for H pylori as recommended above. Alternative therapies-Psychotherapy and hypnother apy may be of benefit in selected motivated patients with. Symptoms and Signs Acute symptoms without abdominal pain are typically caused by food poisoning, infectious gastroenteritis, drugs, or systemic illness. Inquiry should be made into recent changes in medications, diet, other intestinal symptoms, or similar illnesses in family members. The acute onset of severe pain and vomiting suggests peritoneal irritation, acute gastric or intestinal obstruction, or pancreaticobili ary disease. Persistent vomiting suggests pregnancy, gastric outlet obstruction, gastroparesis, intestinal dysmotility, psychogenic disorders, and central nervous system or sys temic disorders. Vomiting that occurs in the morning before breakfast is common with pregnancy, uremia, alcohol intake, and increased intracranial pressure. Vomiting of undigested food one to sev eral hours after meals is characteristic of gastroparesis or a gastric outlet obstruction; physical examination may reveal a succussion splash. Patients with acute or chronic symp toms should be asked about neurologic symptoms (eg, headache, stiff neck, vertigo, and focal paresthesias or weakness) that suggest a central nervous system cause. Special Examinations With vomiting that is severe or protracted, serum electro lytes should be obtained to look for hypokalemia, azote mia, or metabolic alkalosis resulting from loss of gastric contents. Gastroparesis is confirmed by nuclear scintigraphic studies or 1 3 C-octanoic acid breath tests, which show delayed gas tric emptying and either upper endoscopy or barium upper gastrointestinal series showing no evidence of mechanical gastric outlet obstruction. Complications Complications include dehydration, hypokalemia, meta bolic alkalosis, aspiration, rupture of the esophagus (B oer haave syndrome), and bleeding secondary to a mucosal tear at the gastroesophageal junction (Mallory-Weiss syndrome). General Measures Most causes of acute vomiting are mild, self-limited, and require no specific treatment. Patients should ingest clear liquids (broths, tea, soups, carbonated beverages) and small quantities of dry foods (soda crackers). Patients unable to eat and losing gastric fluids may become dehydrated, resulting in hypokalemia with metabolic alka losis. A nasogastric suction tube for gastric or mechanical small bowel obstruction improves patient comfort and permits monitoring of fluid loss. Antiemetic Medications Medications may be given either to prevent or to control vomiting. Combinations of drugs from different classes may provide better control of symptoms with less toxicity in some patients. These agents enhance the efficacy of serotonin receptor antagonists for preventing acute and delayed nau sea and vomiting in patients receiving moderately to highly emetogenic chemotherapy regimens. They are used in 1 combination with corticosteroids and serotonin antago nists for the prevention of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting with highly emetogenic chemotherapy regimens. In patients on mechanical ventilation, hiccups can trigger a full respiratory cycle and result in respiratory alkalosis. Causes of benign, self-limited hiccups include gastric distention (carbonated beverages, air swallowing, overeat ing), sudden temperature changes (hot then cold liquids, hot then cold shower), alcohol ingestion, and states of heightened emotion (excitement, stress, laughing). There are over 100 causes of recurrent or persistent hiccups due to gastrointestinal, central nervous system, cardiovascular, and thoracic disorders. Dopamine antagonists- the phenothiazines, butyro phenones, and substituted benzamides (eg, prochlorpera zine, promethazine) have antiemetic properties that are due to dopaminergic blockade as well as to their sedative effects. High doses of these agents are associated with anti dopaminergic side effects, including extrapyramidal reac tions and depression. With the advent of more effective and safer antiemetics, these agents are infrequently used, mainly in outpatients with minor, self-limited symptoms.

The risk in patients undergoing lower abdominal or pelvic procedures ranges from 2% to 5% spasms back buy generic voveran sr line, and for extremity procedures muscle relaxant parkinsons disease discount voveran sr 100 mg without a prescription, the range is less than 1% to 3% muscle relaxant with ibuprofen order voveran sr. The pulmonary complication rate for laparoscopic pro cedures appears to be much lower than that for open procedures. In one series of over 1 500 patients who under went laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the pulmonary com plication rate was less than 1 %. Other procedure-related risk factors include prolonged anesthesia time, need for general anesthesia, and emergency operations. It remains unclear which of the many patient-specific risk factors that have been identified are independent pre dictors. Surgical patients in their seventh decade had a fourfold higher risk of pulmonary complications compared with patients under age 50. The presence and severity of sys temic disease of any type is associated with pulmonary complications. Patients with well-controlled asthma at the time of sur gery are not at increased risk for pulmonary complications. Obesity causes restrictive pulmonary physiology, which may increase pulmonary risk in surgical patients. Obstruc tive sleep apnea has been associated with a variety of post operative complications, particularly in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. The presence of two or more of these findings had a 78% positive predictive value for obstructive sleep apnea and was associated with a doubled risk for postoperative pulmonary complications. Chest radiographs in unselected patients also rarely add clinically useful information. They may be more useful in patients who are undergoing abdominal or thoracic surgery, who are over age 50, or who have known cardiopulmonary disease. Some experts have also advocated polysomnography to diagnose obstructive sleep apnea prior to bariatric surgery, but the benefits of this approach are unproven. Abnormally low or high blood urea nitrogen levels (indicating malnutrition or kidney disease, respectively) and hypoalbuminemia predict higher risk of pulmonary complications and mortality, although the added value of laboratory testing over clinical assess ment is uncertain. Arterial blood gas measurement is not routinely recommended except in patients with known lung disease and suspected hypoxemia or hypercapnia. Perioperative Management Retrospective studies have shown that smoking cessation reduced the incidence of pulmonary complications, but only if it was initiated at least 1 -2 months before surgery. A meta-analysis of randomized trials found that preoperative smoking cessation programs reduced both pulmonary and surgical wound complications, especially if smoking cessa tion was initiated at least 4 weeks prior to surgery. The preoperative period may be an optimal time to initiate smoking cessation efforts. A systematic review found that smoking cessation programs started in a preoperative evaluation clinic increased the odds of abstinence at 3-6 months by nearly 60%. In three small series of patients with acute viral hepatitis who underwent abdominal surgery, the mortality rate was roughly 10%. Similarly, patients with undiagnosed alco holic hepatitis had high mortality rates when undergoing abdominal surgery. Thus, elective surgery in patients with acute viral or alcoholic hepatitis should be delayed until the acute episode has resolved. In the absence of cirrhosis or synthetic dysfunction, chronic viral hepatitis is unlikely to increase risk significantly. A large cohort study of hepatitis C seropositive patients who underwent surgery found a mortality rate of less than 1 %. Similarly, nonalco holic fatty liver disease without cirrhosis probably does not pose a serious risk in surgical patients. In patients with cirrhosis, postoperative complica tion rates correlate with the severity of liver dysfunction. Traditionally, severity of dysfunction has been assessed with the Child-Turcotte-Pugh score (see Chapter 1 6). Patients with Child-Turcotte-Pugh class C cirrhosis who underwent portosystemic shunt surgery, biliary surgery, or trauma surgery during the 1 970s and 1 980s had a 50-85% mortality rate. Patients with Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A or B cirrhosis who underwent abdominal surgery during the 1 990s, however, had relatively low mortality rates (hepatectomy 0-8%, open cholecystectomy 0 - 1 %, laparo scopic cholecystectomy 0 - 1 %). A conservative approach would be to avoid elective surgery in patients with Child Turcotte-Pugh class C cirrhosis and pursue it with great caution in class B patients. In addition, when surgery is elective, it is prudent to attempt to reduce the severity of ascites, encephalopathy, and coagulopathy preoperatively. Ascites is a particular problem in abdominal operations, where it can lead to wound dehiscence or hernias. Great care should be taken when using analgesics and sedatives, as these can worsen hepatic encephalopathy. Patients with coagulopa thy should receive vitamin K (if there is concern for con comitant malnutrition) and may need fresh frozen plasma transfusion at the time of surgery. Surgery in patients with portal hypertension: a preoperative checklist and strategies for attenuating risk. Patients who are wheezing should receive preoperative therapy with bronchodilators and, in certain cases, corticosteroids. Patients receiving oral theophylline should continue taking the medication perioperatively. Although trial results have been mixed, all these techniques have been shown to reduce the inci dence of postoperative atelectasis and, in a few studies, to reduce the incidence of postoperative pulmonary compli cations. Appropriate preop erative evaluation requires consideration of the effects of anesthesia and surgery on postoperative liver function and of the complications associated with anesthesia and sur gery in patients with preexisting liver disease. The Effects of Anesthesia & Surgery on Liver Function Postoperative elevation of serum aminotransferase levels is a relatively common finding after maj or surgery. Most of these elevations are transient and not associated with hepatic dysfunction. While direct hepatotoxicity is rare with modern anesthetics agents, these medications may cause deterioration of hepatic function via intraoperative reduction in hepatic blood flow leading to ischemic injury. Intraoperative hypotension, hemorrhage, and hypoxemia may also contribute to liver injury. Risk Assessment in Surgical Patients with Liver Disease Screening unselected patients with liver function tests has a low yield and is not recommended. Preoperative anemia is common, with a prevalence of 43% in a large cohort of elderly veterans undergoing surgery. The main goals of the preoperative evaluation of the anemic patient are to determine the need for preoperative diagnostic evaluation and the need for transfusion. When feasible, the diagnostic evaluation of the patient with previously unrecognized anemia should be done prior to surgery because certain types of anemia (particularly those due to sickle cell disease, hemolysis, and acute blood loss) have implications for perioperative management. These types of anemia are typically associated with an elevated reticulo cyte count. While preoperative anemia is associated with higher perioperative morbidity and mortality, it is not known whether correction of preoperative anemia with transfusions or erythropoiesis-stimulating agents will improve postoperative outcomes. Determination of the need for preoperative transfusion in an individual patient must consider factors other than the absolute hemoglobin level, including the presence of cardiopulmonary disease, the type of surgery, and the likely severity of surgical blood loss. The few studies that have compared different postoperative transfusion thresholds failed to demonstrate improved out comes with a more aggressive transfusion strategy. One trial randomized hip fracture patients, most of whom had cardio vascular disease, to either transfusion to maintain a hemo globin level greater than 10 g/dL (1 00 g/L) or transfusion for symptomatic anemia. Patients receiving symptom-triggered transfusion received far fewer units of packed red blood cells without increased mortality or complication rates. The most important component of the bleeding risk assessment is a directed bleeding history (see Table 3 - 1). Labo ratory tests of hemostatic parameters in these patients are generally not needed. When the directed bleeding history is unreliable or incomplete, or when abnormal bleeding is suggested, a formal evaluation of hemostasis should be done prior to surgery and should include measurement of the prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and platelet count (see Chapter 1 3). Patients receiving long-term oral anticoagulation are at risk for thromboembolic complications when an operation requires interruption of this therapy. A randomized trial of bridging anticoagulation in surgical patients taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation demonstrated no difference in thromboembolism. Bleeding complica tions were twice as common in patients who received bridging anticoagulation. Most experts recommend bridg ing therapy only in patients at high risk for thromboembo lism. A n approach to perioperative anticoagulation management is shown in Table 3-5, but the recommenda tions must be considered in the context of patient prefer ence and hemorrhagic risk. There are only limited options to reverse the anticoagulant effect of these medications, so they should only be restarted after surgery when adequate hemostasis is assured. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Throm bosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Postoperative delirium has been associated with higher rates of major postoperative cardiac and pulmonary complications, poor functional recovery, increased length of hospital stay, increased risk of subsequent dementia and functional decline, and increased mortality. Several preoperative and postoperative factors have been associated with the develop ment of postoperative delirium. Delirium occurred in half of the patients with at least three of the risk factors listed in Table 3-7. Two types of intervention to prevent delirium have been evaluated: focused geriatric care and psychotropic medica tions. Common interventions to prevent delirium were minimizing the use of benzodiazepines and anticholinergic medications, maintenance of regular bowel function, and early discon tinuation of urinary catheters. Other studies comparing postoperative care in specialized geriatrics units with stan dard wards have shown similar reductions in the incidence of delirium.

References

- Siroky, M.B., Olsson, C.A., Krane, R.J. The flow rate nomogram: I. Development. J Urol 1979;122:665-668.

- Cicinnati VR, Zhang X, Yu Z, et al. Increased frequencies of CD8+ T lymphocytes recognizing wild-type p53-derived epitopes in peripheral blood correlate with presence of epitope loss tumor variants in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2006;119: 2851-2860.

- Ayabe T, Ashida T, Kohgo Y, Kono T. The role of Paneth cells and their antimicrobial peptides in innate host defense. Trends Microbiol 2004;12:394.

- Toni D, Fiorelli M, Gentile M, et al. Progressing neurological deficit secondary to acute ischemic stroke: Study on predictability, pathogenesis and prognosis. Arch Neurol 1995;52:670-5.

- Freeman RK, Vallieres E, Verrier ED, et al. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: an analysis of the effects of serial surgical debridement on patient mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000; 1119: 260-267.

- Vijayalakshmi IB, Devananda NS, Chitra N. A patient with aneurysms of both aortic coronary sinuses of Valsalva obstructing both ventricular outflow tracts. Cardiol Young. 2009;19:537-9.

- Bulpa PA, Dive AM, Mertens L, et al. Combined bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial lung biopsy: safety and yield in ventilated patients. Eur Respir J 2003;21:489-94.

- Suda K, Murakami I, Katayama T, et al. Reciprocal and complementary role of MET amplification and EGFR T790M mutation in acquired resistance to kinase inhibitors in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:5489-98.