"Buy cheap cefdinir 300mg on-line, virus jewelry".

B. Owen, M.A., M.D., Ph.D.

Deputy Director, Rush Medical College

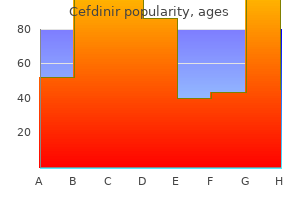

In studies of cerebral organization in individuals who learned English at different times in the life span virus mask discount 300mg cefdinir with mastercard, Neville and colleagues have found that aspects of semantic and grammatical processing differ markedly in the degree to which they depend on the timing of lan- of Sciences antibiotics for uti and exercise 300mg cefdinir sale. In particular antibiotic resistance week safe 300mg cefdinir, in a group of ChineseEnglish bilinguals virus hiv cheap 300 mg cefdinir otc, delays as long as 16 years in exposure to English had very little effect on the organization of the brain systems important in lexical semantics. That is, the brain system underlying the organization of nouns and verbs was disrupted very little. However, delays of only 4 years had significant effects on aspects of brain organization linked to grammatical processing. Brain organization underlying function words, such as prepositions and conjunctions, was severely disrupted. Similar patterns have been found in studies of congenitally deaf individuals who learned English late and as a second language (American Sign Language was their first language). These findings suggest that the systems that mediate the processing of at least some types of grammatical information are much more modifiable by-and therefore vulnerable to-variations in language experience. This is demonstrated again below, in the discussion of interventions with children with specific language disorder. In general, it seems important that practitioners consider the data generated from studies of the effects-and noneffects-of exceptional circumstances on language learning, for they provide important information on the boundary conditions of language learning. Moreover, these phenomena are the anchor points for theories of language development that take into account the resilience of language learning within more normal ranges of both environmental and organic variation. The Impact of Linguistic Input on Language Learning and Language Production As noted earlier, conventional language input is not essential for a young child to develop a language-like system and use it to communicate with others. However, a language model may play a central role in determining how often and when those linguistic properties are used. We noted above, for example, the infrequent use of language to express emotions among children who had been institutionalized. Another example concerns the ability to communicate about objects and events in other than the here and now. Deaf children who are not exposed to usable linguistic input (because their parents do not know American Sign Language, for example) not only use gesture to convey information about the here and now, but they also use it to converse about past, future, and hypothetical events (Morford and Goldin-Meadow, 1997). Linguistic input is thus not essential for a child to communicate about the nonpresent. And the amount and type of talk children hear, in turn, can influence how well they remember events in the past (Reese et al. For example, during the period from 11 to 18 months, children in one study heard, on average, 325 utterances addressed to them per hour (Hart and Risley, 1995). But the range was enormous-one child heard as many as 793 utterances per hours, another as few as 56. The amount of speech children heard from their parents at 18 months was strongly correlated with the amount of speech they heard at age 3. Moreover, these differences tended to be associated with socioeconomic status, although it is important to recognize that the sample of 42 participating families was small and not representative and so cannot provide firm evidence regarding social class differences. Often researchers videotape mothers and their young children to explore parental verbal input and child output. One study (Hoff-Ginsberg, 1991), for example, videotaped mothers while they dressed, fed, and played with their 18- to 29-month-old children. They all talked when they played with their children, but there were big differences in how much they talked and whether they used a rich vocabulary and asked questions during dressing and feeding. The children whose mothers talked more during the mundane activities had larger vocabularies, indicating the importance of integrating conversations throughout the day. It does not explore the role that talk around and about the child might play in language acquisition. This may be particularly important in other cultures, in which children are more likely to be involved in relationships in which skilled conversation takes place around them, but is not directed at them (Rogoff et al. For example, in a Mayan Indian community studied by Rogoff and her colleagues, adults communicated to their children primarily through shared activity and group conversations, rather than in the context of one-on-one lessons or explanations directed to the child. Although, as we noted earlier, virtually all children learn language, the issue is whether there are qualitative differences across individuals that are correlated with differing types of input. It is also important to note that this area of research is open to the criticism that it has not considered the sizeable role that genetic influences undoubtedly play in the development of verbal abilities. Mothers who talk more to their children may also share genetic endowments that facilitate language learning. One study, which took advantage of the fact that twins tend to lag behind singletons in language development, ruled out a variety of competing hypotheses to conclude that the quality and complexity of mother-child communicative interaction was responsible for the twin-singleton differences in language development (Rutter et al.

Risk management decisions depend on the results of risk assessments but may also involve the public health significance of the risk antimicrobial jackets cheap cefdinir 300mg otc, the technical feasibility of achieving various degrees of risk control virus articles discount cefdinir 300mg visa, and the economic and social costs of this control nebulized antibiotics for sinus infection purchase 300 mg cefdinir fast delivery. Risk assessment requires that information be organized in rather specific ways but does not require any specific scientific evaluation methods antibiotics for acne alternatives cefdinir 300 mg discount. Data uncertainties arise during the evaluation of information obtained from the epidemiological and toxicological studies of nutrient intake levels that are the basis for risk assessments. Examples of inferences include the use of data from experimental animals to estimate responses in humans and the selection of uncertainty factors to estimate inter- and intraspecies variabilities in response to toxic substances. Uncertainties arise whenever estimates of adverse health effects in humans are based on extrapolations of data obtained under dissimilar conditions. Options for dealing with uncertainties are discussed below and in detail in Appendix K. The steps of risk assessment as applied to nutrients follow (see also Figure 3-1). Hazard identification involves the collection, organization, and evaluation of all information pertaining to the adverse effects of a given nutrient. It concludes with a summary of the evidence concerning the capacity of the nutrient to cause one or more types of toxicity in humans. Dose-response assessment determines the relationship between nutrient intake (dose) and adverse effect (in terms of incidence and severity). Intake assessment evaluates the distribution of usual total daily nutrient intakes for members of the general population. Risk characterization summarizes the conclusions from Steps 1 and 2 with Step 3 to determine the risk. The risk assessment contains no discussion of recommendations for reducing risk; these are the focus of risk management. Thresholds A principal feature of the risk assessment process for noncarcinogens is the long-standing acceptance that no risk of adverse effects is expected unless a threshold dose (or intake) is exceeded. The critical issues concern the methods used to identify the approximate threshold of toxicity for a large and diverse human population. Because most nutrients are not considered to be carcinogenic in humans, approaches used for carcinogenic risk assessment are not discussed here. The method for identifying thresholds for a general population described here is designed to ensure that almost all members of the population will be protected, but it is not based on an analysis of the theoretical (but practically unattainable) distribution of thresholds. For some nutrients, there may be subpopulations that are not included in the general distribution because of extreme or distinct vulnerabilities to toxicity. These factors are applied consistently when data of specific types and quality are available. This is identified for a specific circumstance in the hazard identification and dose-response assessment steps of the risk. Uncertainty factors are applied in an attempt to deal both with gaps in data and with incomplete knowledge about the inferences required. The problems of both data and inference uncertainties arise in all steps of the risk assessment. A discussion of options available for dealing with these uncertainties is presented below and in greater detail in Appendix K. It is derived by application of the hazard identification and doseresponse evaluation steps (steps 1 and 2) of the risk assessment model. In the intake assessment and risk characterization steps (steps 3 and 4), the distribution of usual intakes for the population is used as a basis for determining whether and to what extent the population is at risk (Figure 3-1). A discussion of other aspects of the risk characterization that may be useful in judging the public health significance of the risk and in risk management decisions is provided in the final section of this chapter, "Risk Characterization. Nonetheless, they may share with other chemicals the production of adverse effects at excessive exposures. Because the consumption of balanced diets is consistent with the development and survival of humankind over many millennia, there is less need for the large uncertainty factors that have been used for the risk assessment of nonessential chemicals. In addition, if data on the adverse effects of nutrients are available primarily from studies in human populations, there will be less uncertainty than is associated with the types of data available on nonessential chemicals. There is no evidence to suggest that nutrients consumed at the recommended intake (the Recommended Dietary Allowance or Adequate Intake) present a risk of adverse effects to the general population. The effects of nutrients from fortified foods or supplements may differ from those of naturally occurring constituents of foods because of the chemical form of the nutrient, the timing of the intake and amount consumed in a single bolus dose, the matrix supplied by the food, and the relation of the nutrient to the other constituents of the diet.

Without this ability infection esbl discount 300mg cefdinir, land management agencies run the risk of recommending unnecessary and expensive treatment strategies virus protection free download cefdinir 300mg visa, or forgoing a much needed rehabilitation technique antimicrobial wash cheap 300 mg cefdinir with amex. A new application to facilitate post-fire recovery and rehabilitation in savanna ecosystems antibiotic resistance kit buy cefdinir 300mg with amex. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Oceanic Engineering Society: Earthzine. The wildfire burden: Why public land seizure proposals would cost western states billions of dollars. Curth, Monica de Torres; Biscayart, Carolina; Ghermandi, Luciana; Pfister, Gabriela. Wildland-urban interface fires and socioeconomic conditions: A case study of a northwestern Patagonia city. The demands and constraints of the postfire environment-primarily the lack of time and access to reliable information and data- will continue to be a source of pressure for agencies and their personnel attempting to plan rehabilitation measures without universal adoption of geospatial tools. To reduce the negative impact that wildfires have on local economies, land management agencies must attempt to use all practicable resources and tools at their disposal to restore or improve public lands following a wildfire. As land management agencies continue to face budget cuts amid congressional and public pressure to streamline their operations and reduce runaway spending, utilizing proven geospatial tools and data to perform previously labor-intensive duties will go a long way toward making wildfire management more efficient. Wildfire policy and public lands: Integrating scientific understanding with social concerns across landscapes. A preliminary report on expenditures and discussion of economic costs resulting from the 2003 Old, Grand Prix and Padua Wildfire Complex. The dynamic path of recreational values following a forest fire: A comparative analysis of states in the Intermountain West. Optimal livestock management on sagebrush rangeland with ecological thresholds, wildfire, and invasive plants. Remote sensing techniques to assess active fire characteristics and post-fire effects. The value of information: Measuring the contribution of space-derived earth science data to resource management. No need to reinvent the wheel: Applying existing social science theories to wildfire. Users, uses, and value of Landsat Satellite Imagery-Results from the 2012 Survey of Users. A hedonic analysis of the short and long-term effects of repeated wildfires on house prices in southern California. Getting ahead of the wildfire problem: Quantifying and mapping management challenges and opportunities. The hidden cost of wildfires: Economic valuation of health effects of wildfire smoke exposure in Southern California. Emergency post-fire rehabilitation treatment effects on burned area ecology and long-term restoration. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences. Challenges of socio-economically evaluating wildfire management on non-industrial private and public forestland in the western United States. The most prominent threat is forest fires because of their impacts on the microhabitat and macrohabitat characteristics and the resulting disruption of ecological processes. Moreover, wildfire aggravates conflicts between humans and wildlife in the forest fringe areas. Spatiotemporally independent fire incidence locations along with other environmental variables were used to build the model. Areas in the projected map were categorized into high fire, marginal fire, and no fire areas. In India, fire affects about 2 to 3 percent of the forested area annually, and on average over 34,000 ha of forests burn each year (Kunwar 2003). Fire hazard is the likelihood of a physical event of a particular magnitude in a given area at a given time, which has the potential to disrupt the functionality of a society, its economy, and its environment (Boonchut 2005). Although fire serves an important function in maintaining the health of certain ecosystems, fires have become a threat to many forests and their biodiversity (Dennis and Meijaard 2001) because of changes in climate and in human use and misuse of fire. Though relocation is being proposed, about 184 Gujjar households were recorded as living inside the sanctuary.

Diseases

- Adult spinal muscular atrophy

- Alopecia immunodeficiency

- Schizoaffective disorder

- Microcephalic primordial dwarfism Toriello type

- XXXX syndrome

- Phosphoglucomutase deficiency type 2