"Discount 20 mg levitra professional mastercard, impotence definition inability".

D. Achmed, M.A., M.D., Ph.D.

Professor, Alpert Medical School at Brown University

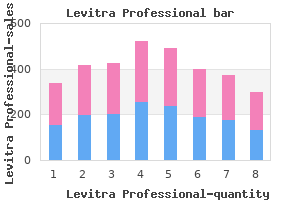

This method is used for a total of 142 countries: all high-income countries except the Netherlands and the United Kingdom; and selected middle-income countries with low levels of underreporting erectile dysfunction fact sheet discount levitra professional 20mg mastercard, including Brazil and the Russian Federation erectile dysfunction treatment seattle generic levitra professional 20 mg on-line. These 142 countries accounted for 6% of the estimated global number of incident cases in 2018 erectile dysfunction age 27 discount levitra professional 20 mg on-line. Green indicates that a source is available erectile dysfunction caused by diabetes discount levitra professional 20mg, orange indicates it will be available in the near future, and red indicates that a source is not available. An assessment is scheduled in Central African Republic in 2019 and a partial assessment has been done in China. If more than two assessments have been done (Pakistan and Zimbabwe), the years of the last two only are shown. Studies in Philippines, South Africa and United Republic of Tanzania are being implemented in 2019. Data for Russian Federation are from routine diagnostic testing of cases (as opposed to a national survey). In addition to national survey data, six countries (Ethiopia, Myanmar, Namibia, Viet Nam, Zambia and Zimbabwe) reported surveillance data from routine diagnostic testing for the first time in 2018. If more than two surveys have been done (Cambodia, Thailand, Philippines), the years of the last two only are shown. This method is used for seven countries: China, Egypt, Indonesia, Iraq, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Yemen. These countries accounted for 18% of the estimated global number of incident cases in 2018. Expert opinion, elicited through regional workshops or country missions, is used to estimate levels of underreporting, overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis. Trends are estimated 1 through mortality data, surveys of the annual risk of infection or exponential interpolation using estimates of case-detection gaps for 3 years. In this report, this method is used for 43 countries that accounted for 16% of the estimated global number of incident cases in 2018. Of the four methods, the last one is the least preferred and it is relied on only if none of the other three methods can be used. Country-specific distributions are used for countries that have implemented a survey; for other countries, the age distribution is predicted using prevalence survey data. Disaggregation by sex is based on actual M:F ratios for countries that have implemented surveys; for other countries, this disaggregation is based on regional M:F ratios from a systematic review and meta-analysis (7). They accounted for 57% of all cases in 2018, compared with 32% of cases in adult women and 11% in children. Case notification data disaggregated by age and sex for people aged 15 years and above were not available for Mozambique. The black solid lines show notifications of new and relapse cases for comparison with estimates of the total incidence rate. Angola 400 300 Bangladesh 60 40 20 0 Brazil 800 600 400 Cambodia 800 600 400 200 0 Central African Rep. Most of these deaths could be prevented with early diagnosis and appropriate treatment (Chapter 1). Millions (2017) a b this is the latest year for which estimates for all causes are currently available. The higher share for children compared with their estimated share of cases (11%) suggests poorer access to diagnosis and treatment.

Syndromes

- Blood tests such as a CBC or blood chemistry

- Malabsorption syndrome (for example, celiac srue)

- Biopsy of affected tissue

- Breathing and airway support

- Bromide poisoning

- To diagnose a urinary tract infection

- How good of a match your donor was

- Loss of body hair and muscle (in men)

Conflict debt index equals the sum total of violent years erectile dysfunction causes diabetes buy levitra professional 20mg on line, where a current violent year equals 1 if the number of deaths per 1 erectile dysfunction injections trimix buy cheap levitra professional 20 mg online,000 population exceeds 0 erectile dysfunction treatment in kl buy 20 mg levitra professional with visa. Earlier conflict years erectile dysfunction causes diabetes discount levitra professional 20 mg amex, similarly defined, are discounted by a decay parameter (see box 3. The conflict scale is divided into three categories: no conflict debt (conflict debt 0. Note: Areas with at least some conflict history have a conflict debt index greater than 0. These varying shares of concentration of the poor in areas with a history of conflict are the consequence of multiple factors, including territorial and population size of the country, proximity to international borders, and age of the conflict, all of which affect the possibility of population displacement. Recurrent conflict, including in the recent past, may prevent a country from repaying its conflict debt, thus perpetuating weak state institutions, retarding human capital accumulation, and obstructing poverty reduction. In contrast, past conflict, even if prolonged, can still be associated with a higher incidence of poverty, but, dynamically, with falling poverty, given a sufficiently long window of sustained peace for poverty reduction to recover after conflict. As the total number of poor and the conflict history for each subnational unit in the data are observed, it is possible to get a sense of the share of the poor in each country who are affected by conflict, particularly by residing in areas with conflict history. Results can be obtained both in the aggregate and separately for different types of conflict history at the subnational level, such as no conflict history; a history of recent conflict, defined as at least one violent year during the past five; and a history of past conflict, defined as having had conflict in the past (with a starting point of 1992), but not in the five years before the year for which poverty data are available. In a number of countries, different groups of poor people may be affected by recent and older conflict history. This half represents 40 percent who are in areas of recent conflict and 10 percent who are in areas of older conflict. In Colombia, where about 10 percent of the poor reside in areas with a conflict history, the majority are in areas with nonrecent conflict. Globally, about 10 percent of the population lives in areas with a conflict history, primarily recent conflict, but also older conflict. In Sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for the bulk of the poor in conflict-affected areas, 30 percent of the population and 35 percent of the poor live in areas with either ongoing or past (primarily recent) conflict. Addressing poverty in areas that have ongoing or recent conflict may require a different set of interventions than in areas with conflict debt from earlier years. For instance, in cases of active conflict, programs aimed at disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration, as well as supporting security and stability and protecting core state and community-based institutions, may be of immediate importance, whereas in countries that are moving out of fragility a broader range of interventions, including those focusing on resource mobilization, service delivery, and macro-fiscal stability, may be warranted (World Bank 2020a). In many cases, however, only a small share of the poor live in specific areas of conflict whereas in others most of the poor are living in areas directly struck by recent conflict. This confluence of poverty and conflict underscores the importance of having policies that differentiate between those who live in areas of high conflict and those who escaped from the area but are still affected by the lingering effects of the conflict. It also calls for policy differentiation across regions, particularly to prevent those localities affected by conflict, recent or past, from suffering from systematic underinvestment and neglect. These distinctions may be important from a policy point of view because poverty in conflict and nonconflict areas may exhibit different trajectories and may be driven by different factors. Note: "Recent conflict" refers to the five-year period ending in the year of the survey providing poverty data, which varies across countries. The fact that the conflict debt effect lingers for years, hindering all sources of development-from human capital to infrastructure, from psychological health to institution building-highlights the importance of prevention to avoid the large and persisting costs of conflict in terms of poverty. A recent World Bank report argues that climate change is another acute threat to poverty reduction, particularly in the economies of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia-the regions where most of the global poor are concentrated (Hallegatte et al. As chapter 1 notes, an update of the methods and data in this report estimates that between 68 million and 132 million people (depending on different scenarios) could be pushed into poverty by 2030 through various channels of climate change impact (Jafino et al. This peril is due to a number of factors, including (1) lower-quality assets, such as lower-quality housing stock or savings through investments in their homes or cattle, which are more vulnerable to damage and loss from floods and droughts; (2) greater reliance on fragile infrastructure, such as unpaved roads, with lower ability to protect against disruptions to infrastructure services; (3) greater dependence on livelihoods derived from agricultural and ecosystems incomes, which are more vulnerable to natural disasters; (4) greater vulnerability to rising food prices in the aftermath of disaster-related supply shocks; and (5) long-term human capital impacts through compromised health and education, including greater susceptibility to climate-related diseases such as diarrhea and malaria (Hallegatte et al. Their analysis, based on 52 countries, shows that, in about half of the countries where the exposure of poor and nonpoor people differs significantly (a third of the overall sample), poor people are overexposed (compared with the nonpoor) to floods at the national level. The relationship between poverty and flood exposure can be complex; at the national level, richer areas (such as economically active coastal towns) are often more exposed, but at the local scale, especially within cities, poor people are much more likely to live in unsafe neighborhoods, often as a result of land market frictions. The present analysis overlays the exposure to flooding on subnational estimates of international poverty for these divisions. Flooding is only one of several types of climate risks and thus does not take into account the impact of droughts, high temperatures, or other natural disasters such as earthquakes or cyclones. The focus on flooding in this section primarily reflects the fact that floods are one of the most common and severe hazards, especially in lower-income countries where infrastructure systems, including drainage and flood protection, tend to be least developed; and there is more local-level variability in the exposure to flooding, in comparison with subnational variation in temperature, which makes the joint exposure to flood risk and poverty at the subnational level more amenable to examination. The focus on flooding does, however, bring to the fore certain countries and regions while not capturing the full extent of disaster risks elsewhere. For instance, river and urban flood risks in countries such as Rwanda are high, whereas the earthquake risk (not related to climate) is medium, and the risk of extreme heat (related to climate) is low.

The State of Alaska incarcerates Alaska Native inmates in detention centers as far away as the State of New York erectile dysfunction shots buy levitra professional 20 mg free shipping. For example erectile dysfunction caused by hydrocodone cheap 20 mg levitra professional with visa, Tribes increasingly contract with other governments to house offenders erectile dysfunction treatment by food order 20mg levitra professional otc. In this situation psychological erectile dysfunction wiki cheap levitra professional 20 mg on line, there may be additional community costs, including transportation and removing scarce policing personnel from the community. Funding has included $225 million in economic stimulus funds for Tribal correctional facility construction. The Indian Law and Order Commission has found these specific issues to be of continuing concern for many other jails in Indian country. Designers of this purposefully built facility, which opened in 2007, did not just focus on meeting the standards necessary for housing a variety of offenders. They also consciously included elements that reflect culture and support rehabilitation. Reentry is a key focus for the corrections center, and it offers classes ranging from basic life skills to vocational certification as a food handler. This innovative spirit has served juvenile offenders well, too: Salt River is the first corrections facility in Indian county to host a full Boys and Girls Club. The partnership was recognized with a Merit Award from the Boys and Girls Clubs of America in 2012. At that time, as many as six inmates were incarcerated in cells designed for one person. The living conditions were so deplorable that no more than two of the six inmates could stand in the cells at any given moment; the rest had to lie or sit on their bunks. Because of the "thinness" of the overall institutional and service provision environments in which most operate, Tribal jails may need to provide more services, at greater cost, than non Tribal jails. These facilities serve at least three distinct purposes: pretrial detention, short-term incarceration for nonviolent offenders, and longer term incarceration for violent offenders. The facilities must serve multiple populations: men and women, and sometimes both adults and juveniles. Using average daily census as the basis for per prisoner cost comparison, Tribal jails operate with fewer resources than one-quarter of State prison systems Maine, Minnesota, North Dakota, Washington, and California (States with significant Native populations), are all part of this upper quartile. Tribal jails that operate closer to their rated inmate capacity fare much worse They must fulfill their many functions with resources comparable to those available to a rural county lock-up up or a Federal low-security prison. In both 2011 and 2012, one out of five Indian country jails operated at 150 percent of their rated capacity on their most crowded days. For at least six of these jails, adequate space may be a more constant concern, as they reported overcrowded conditions not only on peak days, but also on randomly sampled dates. Heffelfinger told the Star Tribune that the delay on opening the facility is "ridiculous. Eric Roper, "Red Lake Lockup Sits Locked Up and Empty," Star Tribune March 21, 2010 124 A Roadmap for Making Native America Safer Table 5. County jail costs vary significantly based on size, location, and services offered. Nathan James, the Federal Prison Population Build Up: Overview, Policy Changes, Issues, and Options, Congressional Research Service 15 (2013). Gary Zajac & Lindsay Kowalski, An Examination of Pennsylvania Rural County Jails 14, the Center for Rural Pennsylvania (December 2012) ("The system-wide average cost-per-day, per-inmate was $60. Christian Henrichson & Ruth Delaney, the Price of Prisons: What Incarceration Costs Taxpayers 10, fig. The collaboration, which combines the jurisdiction of the Tribe with the federally transferred jurisdiction the State exercises under P. Judges from the Tribe and county preside over the court together, which creates trust between the Tribe and county. By 2012, the recidivism rate among offenders processed through the joint jurisdictional court reach only 4 percent, a marked decrease from the rates of 60-70 percent that had prevailed before the court came into operation. However, the most telling sign of success is the change in attitude of the community.

This recommendation is a detention-specific version of the recommendations for increased intergovernmental collaboration made elsewhere in this report erectile dysfunction 17 discount 20 mg levitra professional with amex. This includes any funds specifically intended for Tribal jails and other Tribal corrections programs impotence beta blockers buy cheap levitra professional 20 mg online. To the extent that alternatives to detention eventually reduce necessary prison and jail time for Tribal-citizen offenders erectile dysfunction medicine in bangladesh buy discount levitra professional 20 mg on-line, savings should be reinvested in Indian country corrections programs and not be used as a justification for decreased funding erectile dysfunction causes heart levitra professional 20mg. The Commission has two major concerns with regard to funding for Indian country corrections. The first is that Tribes must receive a fair share of funds available at the Federal level for corrections systems creation and operation. While some corrections funds are specifically designated for Tribes, most are allocated in a manner that privileges State and local governments above Tribal governments. New approaches to funding should ensure that Tribes are treated equally in the allocation of resources. In the event that the detailed accounting needed to enable such a system proves to be impractical, some scaled-down or simplified version of this "follow the offender" system would still be worthwhile to make the Federal government accountable about the realdollar value of its investments in Indian country justice programming. Success with alternatives to detention should allow a reprioritization of spending without reducing the pool of money available to Indian country. Similarly, any given Tribe should realize savings it generates through community supervision and reductions in recidivism. Department of Justice should provide incentives for the development of high-quality regional Indian country detention facilities, capable of housing offenders in need of higher security and providing programming beyond "warehousing," by prioritizing these facilities in their funding authorization and investment decisions; and, b) Congress should convert the Bureau of Prisons pilot program created by the Tribal Law and Order Act into a permanent programmatic option that Tribes can use to house prisoners. While this approach would mean that some prisoners are housed farther from their home communities than may be ideal, the increased use of alternatives to detention will limit the use of incarceration to those offenders for whom detention makes the most sense. Other offenders will remain in the community under probation and other types of community supervision, which keeps them close to home. Among the few Tribes that have done so or attempted to , the administrative hurdles are significant, and a reduction in these barriers would increase Tribal access. Conclusion Despite a growing number of higher-quality detention facilities in Indian country, there is a tremendous need for Tribes and the Federal government to collaborate on improving the condition, programs and services, and functionality of facilities. At the same time, Tribes are deeply interested in expanding available alternatives to detention in their communities. Certainly, upfront investments in improved detention facilities and the creation of quality alternatives to detention programs are necessary. But, because of the substantial cost savings associated with effective alternative programs, the spending profile may soon reflect a redirection of detention dollars, rather than an ongoing need for higher budgets. It can also make Native nations safer and more secure-thereby helping close the public safety gap-by relying on locally based systems that more accurately teach and enforce community values. Despite its remarkable longevity and pervasive impact in Indian country, the Major Crimes Act was attached to the annual congressional appropriations bill for 1885 as a so-called "rider" and never received a legislative hearing in either house of Congress. Eid and Carrie Covington Doyle, Separate But Unequal: the Federal Criminal Justice System in Indian Country, 81 U. Delone, Sentencing of Native Americans: A Multistage Analysis Under the Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines, 8 J. Droske, Correcting Native American Sentencing Disparity Post-Booker, 91 Marquette L. See Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs, Overview of Correctional Facilities on Tribal Lands. Pre-trial detainees composed a consistent 39-44 percent of the tribal jail population over the period 2000-2012. Warren, Evidence-Based Practice to Reduce Recidivism: Implications for State Judiciaries, the Crime and Justice Institute, the National Institute of Corrections, & Community Corrections Division 24 (2007) (finding that well-implemented rehabilitation and treatment programs carefully targeted with the assistance of validated risk/needs-assessment tools at the right offenders can reduce recidivism by 10% to 20%"), static. Other key literature on the success of alternatives to detention include Michelle Evans-Chase & Huiquan Zhou, A Systematic Review of the Juvenile Justice Intervention Literature: What It Can (and Cannot) Tell Us About What Works With Delinquent Youth, 10 Crime & Delinquency 1 (December 2012) dx. Comparison across studies suggests that ome programs achieve reductions in recidivism even greater than 20%. The final sections of this compendium list the non-monetary benefits that derive from drug courts, a type of alternative sentencing. Administrative Office of the Courts, Center for Families, Children, and the Courts, Research Summary: California Drug Court Cost Analysis Study 5 (May 2006). Mitchell, & Cynthia Leyba, Smaller, Smarter and More Strategic: Juvenile Justice Reform in Bernalillo County, Bernalillo County Youth Services Center Juvenile Detention Alternative Initiative (2011). Casey Foundation, No Place For Kids the Case for Reducing Juvenile Incarceration (2011).